Acting Deputy Commissioner for Retirement and Disability Policy,

Social Security Administration

before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

Subcommittee on Energy Policy, Heath Care and Entitlements

April 9, 2014

Chairman Lankford, Ranking Member Speier, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for this opportunity to continue the conversation from last November’s hearing and the follow-up discussion in December on the disability programs we administer at the Social Security Administration (SSA). We share your commitment to effective oversight of Federal benefit programs, so that they remain strong for those who need them.

The responsibilities with which we have been entrusted are immense in scope. To illustrate, in fiscal year (FY) 2013 we performed the following for Social Security and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) beneficiaries:

- Paid over $850 billion to more than 62 million beneficiaries, of whom about 15 million received approximately $175 billion in benefits under our disability programs (About 3 million of our beneficiaries receive benefits under more than one program);

- Handled over 53 million transactions on our National 800 Number Network;

- Received over 68 million calls to field offices nationwide;

- Served more than 43 million visitors in over 1,200 field offices nationwide;

- Completed nearly 8 million claims for benefits and nearly 794,000 hearing dispositions; and

- Completed 429,000 full medical continuing disability reviews (CDR).

Today, my testimony focuses on medical CDRs and age 18 redeterminations. We conduct medical CDRs and age 18 redeterminations to ensure that only those beneficiaries who remain disabled continue to receive monthly benefits.

I begin with a very brief overview of our disability programs and the legislative history of CDRs and age 18 redeterminations. I’ll then discuss where we stand today in conducting these critical program integrity reviews, including our plans for processing them under the President’s FY 2015 Budget Request.

The Disability Programs We Administer

Under the Social Security Act (Act), we administer two major programs that provide cash benefits to persons with disabling physical and mental disorders: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the SSI program.

The SSDI program provides benefits to disabled workers and their dependents. Workers become insured under the SSDI program based on contributions to the Social Security trust funds through taxes on their wages and self-employment income. Thus, SSDI benefits are commonly called “earned benefits.” Under the Act, most SSDI beneficiaries are eligible for Medicare after being entitled to cash benefits for 24 months.

SSI is a Federal means-tested program funded by general tax revenues and designed to provide cash assistance to aged, blind, or disabled persons with little or no income or resources to meet their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter. In addition to cash payments, most SSI beneficiaries are eligible for Medicaid health insurance coverage from the States.

Definition of Disability

For adults under both the SSDI and SSI disability programs, the Act generally defines disability as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity1 due to a severe, medically determinable physical or mental impairment that has lasted or is expected to last for at least one year or to result in death.2 This is a very strict definition of disability when compared to definitions in many commercially available long-term disability policies.

Legislative History of CDRs and Age 18 Redeterminations

When Congress created the SSDI program under the “Social Security Amendments of 1956,”3 it included a mechanism for SSA to monitor a disability beneficiary’s continued eligibility by adding section 225 to the Act.4 This section authorized SSA to suspend the benefits and review the medical conditions of those beneficiaries believed by SSA to no longer have a disabling condition. Such reviews are generally conducted by examiners in the Federally-funded State Disability Determination Services (DDS), which also are responsible for making initial determinations of disability.

In its report accompanying the “Social Security Amendments of 1965,”5 the House Committee on Ways and Means articulated its expectation that “procedures will be utilized to assure that the worker’s condition will be reviewed periodically and reports of medical reexaminations obtained” so that benefits would be “promptly” terminated if a worker’s disability ceased.6

Under SSA policy from 1969 until 1976, medical improvement had to be shown before an adjudicator could cease a beneficiary’s benefits.7 According to a 1975 House Subcommittee on Social Security staff survey, almost all DDSs cited this requirement as a problem; they believed it allowed some beneficiaries to continue receiving disability benefits they should not have received in the first place.8 In July 1976, SSA eliminated this requirement; instead, an adjudicator could treat the case as if it were an initial decision.9

By 1978, SSA’s monitoring activities had significantly dropped due to an increase in the size and complexity of its other workloads. The number of CDRs per 1,000 beneficiaries fell from approximately 111.8 in 1970 to a low of 29 in 1978.10 Consequently, there were fewer disability cessations. These circumstances raised congressional concerns that SSA was not properly monitoring the ongoing medical condition of its disability beneficiaries.

To address this problem, the “Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980” added section 221(i) to the Act.11 This provision required SSA to review the cases of SSDI beneficiaries with nonpermanent disabilities at least once every three years, and those with permanent disabilities at less frequent intervals to be determined by SSA. Although the law required these reviews to begin in January 1982, SSA began the periodic review process in March 1981. From FYs 1981 to 1983, SSA—mainly through the DDSs—conducted nearly 1.3 million CDRs.12

Shortly thereafter, media reports began to surface of people dying after their SSDI and SSI benefits had been discontinued. There was also great concern about the large number of disabled beneficiaries whose benefits had been terminated due to CDRs.13 In 1983, governors or Federal courts ordered 18 DDSs to provide evidence of medical improvement before terminating disability benefits. Eight more governors ordered DDSs to discontinue processing benefit terminations. As the year progressed, this situation worsened and, on December 7, 1983, SSA advised all DDSs to temporarily stop processing benefit terminations. As a result of this moratorium, a backlog of pending CDRs began to develop.14

Concerned about the erosion of public confidence in the disability program, Congress passed the “Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984.”15 Section 2 of this law amended sections 223(f) and 1614(a) of the Act by establishing a Medical Improvement Review Standard (MIRS) for CDR cases.16 SSA issued final MIRS regulations on December 6, 1985. These regulations define “medical improvement” as any decrease in the medical severity of the beneficiary’s impairment(s), which was present at the time of the most recent favorable medical decision that he or she was disabled or continued to be disabled. In addition, the statute and SSA’s rules generally require that, even if the beneficiary’s condition has medically improved, the improvement must be related to his or her ability to work before benefits may be terminated. CDRs were resumed at a diminished pace in 1986.

By the early 1990s, Congress was again taking notice of the CDR backlog and the difficulty the agency was having with balancing initial claims processing and program integrity reviews in an environment of increased workload pressures.17 In response to these concerns, Congress passed several laws aimed at increasing the number of CDRs SSA conducted.

First, the “Social Security Independence and Program Improvements Act of 1994” directed SSA to conduct CDRs on at least 100,000 SSI recipients during each of FYs 1996, 1997, and 1998.18 It also required SSA to redetermine the eligibility of at least one-third of all childhood SSI recipients who reached age 18 during FYs 1996-1998 within one year after they turned 18.19

The “Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996” followed and included a provision authorizing the appropriation of special funds to be used exclusively to conduct additional CDRs over a seven-year period.

20 That same year, “The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996,” required SSA to:

- Conduct CDRs at least once every 3 years for SSI disability recipients under age 18 whose conditions were likely to improve;

- Redetermine the eligibility of an SSI recipient using the adult criteria for initial eligibility during the one-year period beginning on the individual’s 18th birthday; and

- Conduct CDRs no later than 12 months after birth for recipients whose low birth weight is a contributing factor material to the agency’s finding of disability.21

The “Balanced Budget Act of 1997” fine-tuned these changes. It permitted SSA to schedule CDRs for low birth-weight babies at a date after the first birthday if the agency determined the impairment is not expected to improve within 12 months of the child’s birth. It also allowed SSA to make redeterminations of disabled childhood recipients who attain age 18, using the adult eligibility criteria for initial claims, either during the one-year period beginning on the individual’s 18th birthday, or in lieu of a CDR, whenever SSA determines that an individual’s case is subject to such a redetermination.22

The “Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999” included several modifications to the CDR process. Among them, it prohibited the initiation of a CDR for disability beneficiaries who were participating in the Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency Program.23

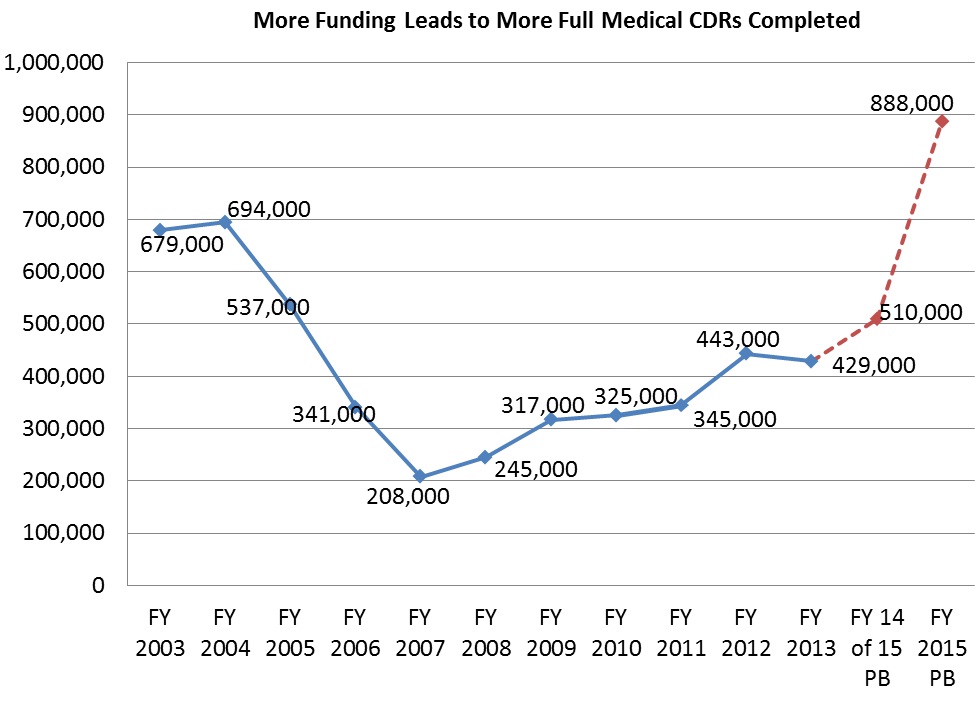

Most recently, the “Budget Control Act of 2011” (BCA) authorized additional funding over a 10-year period so that the agency could essentially eliminate the backlog of CDRs, as well as increase the volume of SSI non-medical redeterminations.24 As the chart (below) shows, the current backlog of CDRs developed due to lower volumes of CDR processing over most of the last decade, which occurred because of budgetary shortfalls.

Regrettably, Congress did not fully fund the additional program integrity spending it authorized for appropriation during the first two years of the BCA’s 10-year period. For FY 2014, it did fully fund the additional resources it had authorized.

The CDR Process and How We Ensure Quality

As mentioned earlier, we periodically conduct medical CDRs to evaluate whether SSDI and SSI beneficiaries continue to meet the medical criteria for disability. We also conduct medical CDRs when we receive a report of medical improvement from a beneficiary or third party.

We complete medical CDRs in two ways, which together ensure that we are targeting our resources to the most problematic areas in the most cost-effective way. To ensure that we are focusing our efforts on the cases with the highest likelihood of medical improvement, we employ a statistical modeling system that uses data from our records to determine the likelihood that a disabled beneficiary has improved medically. We began using models to focus our efforts in 1993 and have been continuously reviewing, validating, and updating them in collaboration with the best outside experts in this field. If the statistical modeling system indicates that the beneficiary has a higher likelihood of medical improvement, we send the case to the State DDS for a full medical review.25

The remaining beneficiaries who are due for review but have a lower likelihood of medical improvement receive a questionnaire requesting updates on their impairments, medical treatment, and work activities. If the completed mailer indicates that there has been potential medical improvement, we send the case to the DDS for a full medical review. Otherwise, we reschedule the case for a future review.26 Since 1996, we estimate that, on average, medical CDRs yield at least $10 in net Federal lifetime program savings per dollar spent, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid.

As history has shown, we produce results when we receive adequate funding for CDRs. For example, by the time the seven-year commitment of special funding we received in FY 1996 expired at the end of FY 2002, we had completed approximately 9.4 million CDRs (including 4.7 million full medical reviews) and were current on all CDRs that were due. For all the medical CDRs completed during the period of FYs 1996 through 2002, we spent roughly $3.4 billion, with an estimated associated lifetime savings from this activity of approximately $36 billion.

We go to great lengths to ensure that CDRs are done right and that their outcomes flow from consistent application of policy. We require all of the DDSs to have an internal quality assurance (QA) function. In addition, we conduct QA reviews of DDS CDR determinations. These reviews show that the DDSs have maintained a high CDR decisional accuracy rate— approximately 97.2 percent in FY 2013.27

In addition to our QA reviews of CDRs, the Act requires that we review at least 50 percent of all DDS initial and reconsideration allowances for SSDI and SSI disability for adults. These pre-effectuation reviews allow us to correct errors we find before we issue a final decision. The reviews of allowances and continuances done in FY 2011 resulted in an estimated $751 million in lifetime net Federal program savings, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid. Based on our estimates for the reviews done in FY 2011, the return on investment is an average of roughly $13 in net Federal savings per $1 of the total cost of the reviews.28

CDRs in the FY 2015 President’s Budget

Earlier, I touched upon Congress not appropriating the full program integrity amounts it authorized for us in the BCA in each of the first two years following enactment. For this reason, we were not able to increase our CDR levels during that period. This fiscal year, however, we will be able to expand our capacity to complete more of our cost-effective CDRs, because Congress appropriated the full BCA level. We plan to aggressively hire and train employees in FY 2014, allowing us to complete more CDRs and set the stage for handling even more in FY 2015.

In FY 2015, the President’s Budget is once again requesting the full BCA level of program integrity funding for SSA, or $1.396 billion. With this funding, we plan to complete 888,000 full medical CDRs. For comparison, we completed 429,000 full medical CDRs in FY 2013, and we plan to complete 510,000 full medical CDRs in FY 2014.

Starting in FY 2016, the budget proposes to repeal the discretionary cap adjustments enacted in the “Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985,”29 as amended by the BCA, for SSA and instead provide a dedicated, dependable source of mandatory funding for SSA to conduct CDRs, as well as SSI non-medical redeterminations. The proposal includes the creation of a new account called Program Integrity Administrative Expenses, which will reflect mandatory funding for SSA’s program integrity activities. The mandatory funding will enable us to work down a backlog of 1.3 million medical CDRs.

As a result of the discretionary funding in 2015 and the mandatory funding in 2016 through 2024, we will recoup a net savings of nearly $35 billion in the 10-year window and additional savings in the out-years.30

Conclusion

We need your support of the President’s FY 2015 Budget Request for our agency to continue ensuring that only those beneficiaries who remain disabled continue to receive benefits. As history has shown, the provision (or availability) of timely, sustained, and adequate resources is the single most important way to ensure that backlogs do not develop in program integrity reviews. We welcome continued collaboration with the Subcommittee to identify new opportunities that may further strengthen our program integrity review process.

__________________________________________________________

1 Substantial gainful activity, or SGA, refers to the performance of significant physical or mental activities in work activity of a type generally performed for pay or profit. SGA is a test for determining initial eligibility for both the SSDI and SSI disability programs, as well as a test for determining continuing eligibility under SSDI. Generally, countable earnings averaging over $1,070 a month (in 2014) demonstrate the ability to perform SGA. For blind persons, countable earnings averaging over $1,800 a month (in 2014) demonstrate SGA for SSDI. These amounts, however, are subject to modifications and exceptions based on very complex statutory incentives designed to encourage work.

2 We also have an SSI disability program for children under age 18. To qualify for SSI benefits based on a disability, a child must have a physical or mental condition that results in marked and severe functional limitations. This condition must have lasted, or be expected to last, at least one year or result in death.

3 P.L. 84-880.

4 U.S. Senate. Committee on Finance. “Staff Data and Materials Related to the Social Security Disability Insurance Program.” (S. Prt. 97-16). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1982, at 48.

5 P.L. 89-97.

6 U.S. House. Committee on Ways and Means. “Report on H.R. 6675.” (H. Rpt. 89-213). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1965, at 89.

7 U.S. House. Committee on Ways and Means. “Report to Accompany H.R. 3755.” (H. Rpt. 98-618). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1984, at 9.

8 U.S. House. Committee on Ways and Means. “Status of the Disability Insurance Program.” (H. Prt. 97-3). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1981, at 10-11.

9 Ibid.

10 U.S. Senate. Committee on Finance. “Staff Data and Materials Related to the Social Security Disability Insurance Program.” (S. Prt. 97-16). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1982, at 49.

11 P.L. 96-265, section 311.

12 “Timeline History of Continuing Disability Reviews,” SSA/Office of Disability and Income Security Programs Archival Document, circa 1995.

13 For example, see Engel, Margaret. “Eligible Recipients Losing Out; U.S. Gets Tough With Disabled.” The Washington Post 7 Sept. 1982: A1. Print.

14 U.S. General Accounting Office. “Social Security Disability: Implementation of the Medical Improvement Review Standard.” December 1986, at 8.

15 U.S. House. Committee on Ways and Means. “Report to Accompany H.R. 3755.” (H. Rpt. 98-618). Washington: Government Printing Office, 1984, at 2.

16 P.L. 98-460, section 2.

17 For example, see the written statement of Jane L. Ross, Associate Director, Income Security Issues, Human Resources Division, General Accounting Office, submitted to the House Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security, March 25, 1993.

18 P.L. 103-296, section 208.

19 P.L. 103-296, section 207.

20 P.L. 104-121, section 103.

21 P.L. 104-193, section 212.

22 P.L. 105-33, section 5522.

23 P.L. 106-170, section 101. In addition, under section 111, it prohibited scheduling a CDR based on work activity for disability beneficiaries who received at least 24 months of benefits, or using the work activity of those beneficiaries as evidence that the individual is no longer disabled. These individuals would still be subject to a regularly scheduled CDR that is not triggered by work and termination of benefits if the individuals’ earnings exceeded the SGA level.

24 P.L. 112-25, section 101.

25 Once we determine which CDRs are eligible for full medical reviews, we prioritize statutorily mandated reviews for release, which include age 18 redeterminations and low birth-weight baby cases.

26 Each year, we validate the mailer process by performing full medical reviews of cases in which we otherwise would have used the mailer process to ensure that the mailer process is properly identifying individuals who continue to be disabled. These cases and the hundreds of thousands of other similar cases we reviewed in prior years confirm that the mailer process is a sound, efficient way to conduct CDRs for most individuals.

27 The percent is based upon a statistically valid sample of case reviews. It reflects the percent of cases reviewed where we agree with the decision made by the DDS.

28 Details can be found in the “Annual Report on Social Security Pre-effectuation Reviews of Favorable State Disability Determinations” at http://ssa.gov/legislation/PER%20fy11.pdf.

29 P.L. 99-177.

30 Office of Management and Budget. “Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2015.” Washington: Government Printing Office, 2014, at 119.