Statement of Robert W. Williams

Associate Commissioner, Office of Employment Support Programs

before the House Committee On Ways and Means,

Subcommittee on Social Security

and

the Subcommittee on Human Resources

September 23, 2011

Chairman Johnson, Chairman Davis, and Members of the Subcommittees:

I am privileged and pleased to discuss the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) efforts to help beneficiaries with disabilities return to work.

We serve a diverse population of people with disabilities through the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs. Our beneficiaries have a wide-range of impairments and represent diverse age groups, levels of education, work experience, and capacities for working. Despite significant challenges, helping these beneficiaries take advantage of employment opportunities remains one of our highest priorities. While we are not where we want to be, we are making progress and building on our commitment that began over 50 years ago to help beneficiaries return to work.

I accepted the position of Acting Associate Commissioner for Employment Support Programs a few months ago for a couple of reasons. The first is that my own life and career convince me that many more Americans with significant disabilities can work and become fully self-supporting, if they receive the right opportunities and support. Second, I think we have an opportunity to “right-size” expectations for the Ticket to Work program and our other employment support programs.

We need to be realistic and strategic about the number of beneficiaries who will become financially independent due to work and earnings, even in the best of economies.

We must also ensure that the Ticket program and our other work incentives provide a path to good jobs, good careers, and better self-supporting futures. Frankly, it is the only way we can create an environment to help more beneficiaries actually leave the disability rolls.

It is time to change our “any job will do” mentality of job placement, where we focused on getting beneficiaries into low wage, marginal jobs that offer little in the way of either security or a better life. We need to focus less on the numbers of beneficiaries who work just above the substantial gainful activity level and focus instead on the quality of support services we provide and outcomes we produce for those beneficiaries. If we truly want to produce positive outcomes for the Vocational Rehabilitation (VR), Ticket, and Work Incentives Planning and Assistance (WIPA) programs, the best way of doing so is by improving how we recognize, support, and reinforce, the initiative and financial independence of these American workers.

We have a number of return to work efforts in place and are currently testing what we hope will be some promising initiatives.

Work Incentives

The Social Security Act (Act) includes a number of incentives to encourage disability beneficiaries to return to work. Generally, these incentives provide beneficiaries with continued benefits and medical coverage while working or pursuing an employment goal. For example, in the SSDI program, the incentives include the trial work period and the extended period of eligibility. In the SSI program, work incentives include more beneficial rules for counting income from earnings and the Plan to Achieve Self-Support. In addition, special rules about impairment-related work expenses, expedited reinstatement, and medical insurance apply to both SSDI and SSI disability beneficiaries. In the Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 (Ticket Act), Congress also created ways for individuals to maintain their Medicare and Medicaid coverage even after they have become fully self-supporting and earned their way off SSDI or SSI. A more comprehensive description of our work incentives is available at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/redbook/.

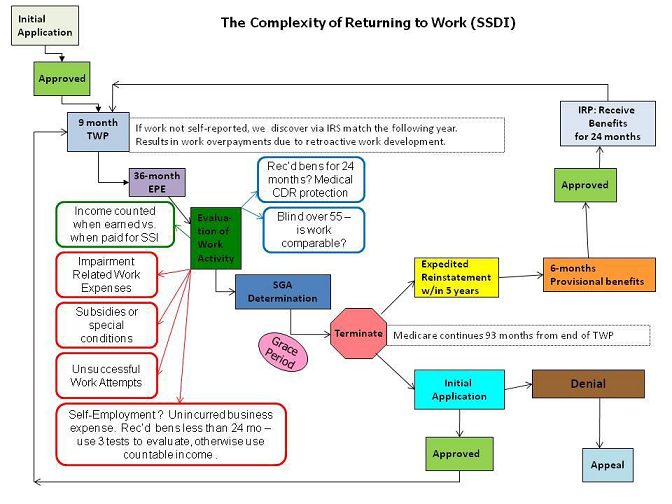

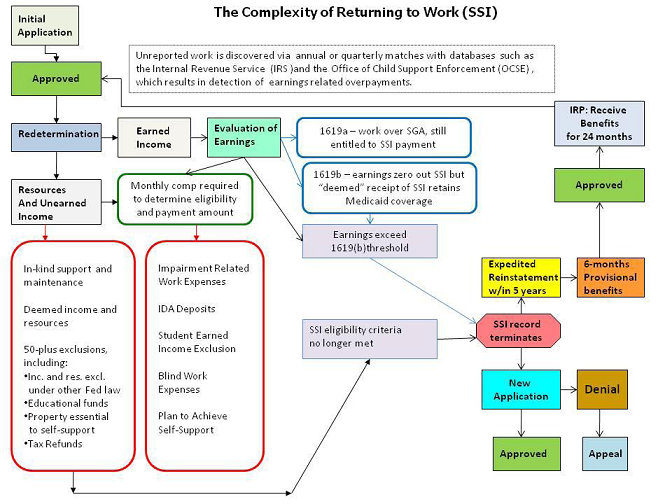

We have trained our field office personnel to explain the work incentives, and we publish information on our website and in publications to help people understand the provisions. Nevertheless, our work incentive provisions are complex and difficult to administer and to understand as illustrated by these two charts. Because the work incentive rules are different for SSDI than they are for SSI, the situation is even more complex if a person is entitled to both types of benefits.

While we work to improve our supports for our disability beneficiaries, we believe that one of the best things we can do for them would be to simplify our work incentive rules.

The FY 2012 President’s Budget includes a legislative proposal to reauthorize for five years our section 234 demonstration authority for Disability Insurance (DI), which allows us to use Trust Fund monies to conduct various demonstration projects, including alternative methods of treating work activity of DI beneficiaries. The President’s Budget also includes a proposal that would authorize us to conduct the Work Incentives Simplification Pilot (WISP). We would use WISP to test important improvements in our return-to-work rules, subject to rigorous evaluation protocols. WISP would eliminate current barriers to employment by simplifying the treatment of beneficiaries’ earnings, potentially reducing improper payments.

The Ticket to Work Program

Prior to the Ticket program, State Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) agencies were the primary entities that provided return-to-work services at no cost to beneficiaries. We continue to reimburse the State VR agency’s costs if a beneficiary engages in substantial gainful activity (SGA) for nine consecutive months.

Congress established the Ticket program in 1999 to expand the universe of service providers and to provide beneficiaries with choices beyond the State VR agencies to obtain the services and supports they need to maintain employment.

The Ticket program can be valuable even if it helps only a small number of beneficiaries return to work. Each disability award is expensive; on average, an award costs $250,000 in DI benefits and Medicare costs over a beneficiary’s lifetime. To the extent that we get some of our beneficiaries back to work and off the disability rolls, we will save a portion of those program costs; it does not take many beneficiaries to return to work for those savings to add up. Thus, it does not take very many exits from the disability rolls to pay for the cost of the Ticket program.

Ticket Program Overview

Under our current Ticket program rules, an adult SSDI or SSI beneficiary can receive a Ticket. A beneficiary who is eligible to participate in the Ticket program may choose to assign his or her Ticket to an Employment Network (EN). We contract with ENs, which are qualified State, local, or private organizations, to provide or coordinate the delivery of employment support services to our disability beneficiaries. Some State VR agencies also act as ENs. We also work closely with the Department of Labor (DOL) to expand the services and supports available to our beneficiaries through DOL’s national network of workforce investment boards and One-Stop Career Centers.

Beneficiaries, ENs, One-Stop Career Centers, and State VR agencies voluntarily participate in the Ticket program. An EN decides whether to accept a Ticket from the beneficiary. Once a beneficiary assigns a Ticket to an EN, the EN provides employment support services to assist the beneficiary in obtaining self-supporting employment. The beneficiary receives these services at no charge.

Consistent with Congressional intent, we pay an EN only when it is successful in assisting beneficiaries secure and maintain employment.

Ticket Program Implementation

We completed implementation of the Ticket program in September 2004. Early experience showed that the program did not increase beneficiary choice or increase work outcomes as much as we would have liked.

Our initial Ticket regulations contributed to this problem. The regulations set the outcome payment amounts too low and the bar for receiving those payments too high. This unappealing combination discouraged service providers from becoming ENs.

To address these concerns, we developed new Ticket regulations that became effective on July 21, 2008 and made several key changes. We created a more attractive payment structure by increasing payment rates to ENs. Moreover, we increased available services by permitting State VR agencies to work collaboratively with ENs in an arrangement known as Partnership Plus. This team approach allows State VR agencies to provide training and job placement services and then refer beneficiaries to ENs that can offer ongoing job retention support. This initiative increases the likelihood that beneficiaries will keep working, become self-supporting, and leave the rolls.

The 2008 regulations have significantly increased beneficiary and EN participation in the Ticket program. As of September 1, 2011, there were over 41,000 Tickets assigned to ENs; this figure represents nearly a 200 percent increase from May 1, 2008. Over this same period, the number of active ENs increased by nearly 50 percent, and the number of beneficiaries that ENs placed in a job increased by almost 300 percent (from a little over 4,000 beneficiaries to over 15,800 beneficiaries).

Let me share one compelling Ticket success story. Walgreens has signed on to serve as an EN and reconfigured its work processes to support workers with cognitive impairments. To date, two Walgreens distribution centers have hired ten Ticket beneficiaries on a full-time basis. Each one of those ten beneficiaries has worked his or her way off of the disability rolls.

Despite these strides, there are issues slowing the Ticket program’s progress, and we are working to address them. This May, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report on the Ticket program. Based on the report’s findings, we have enhanced our quality assurance oversight and developed a performance measurement system to assess whether ENs are meeting our beneficiaries’ needs.

Ticket Program Outreach Activities

In addition to revising our regulations, we are targeting our EN recruitment to those employment service providers with the ability to provide ongoing supports to our beneficiaries that will lead to good jobs, good careers, and better self-supporting futures. In particular, we are concentrating our efforts on recruiting qualified ENs to participate in the Partnership Plus initiative and recruiting workforce investment boards (State legal entities that operate One-Stop Career Center locations for the DOL). Working with the DOL, 122 workforce investment boards have become ENs, and they provide return-to-work services in 421 One-Stop Career Center locations. We also have about 20 new agencies in the pipeline.

We are using our management information to target our outreach to beneficiaries. Based on several years experience with Work Incentive Seminar events, we are now re-focusing our outreach efforts to those beneficiaries who are most likely to return to work, and we are using more efficient methods, like webinars, to reach them.

Improving the Ticket Program

I will discuss briefly the additional steps we are planning to improve the Ticket program further.

First, we would like to gain a deeper understanding of how former beneficiaries fare after they earn their way off the rolls. We plan to analyze data to identify needs, characteristics, and experiences of these former beneficiaries to improve our return to work and job retention efforts.

Next, we will target our marketing of the Ticket program to the beneficiaries who are most likely to use it. Those beneficiaries tend to be under age 40. We will also seek ways to increase the Ticket program’s use by beneficiaries who are between ages 40 and 54.

Finally, we want to help Ticket beneficiaries secure higher-paying jobs. We believe these jobs would enable many beneficiaries to earn significantly more than they would have had by keeping their earnings under the SGA level to remain on benefits. If Ticket holders can gain and sustain such employment, we would create an accessible pathway to self-sufficiency.

These steps will foster the level of beneficiary work activity Congress envisioned when it passed the Ticket Act and help beneficiaries imagine and invest in futures far different from what seem possible today. They would create accessible pathways that beneficiaries could use to return to work, achieve financial independence, and live the American Dream.

Other Return to Work Efforts

I would like to touch upon a few other employment support efforts.

The Ticket Act created two programs to supplement the assistance available at our field offices and help beneficiaries understand our work incentive rules. The two programs provide grants to organizations with ties to the disability community at the local level. These services are available to all SSDI and SSI beneficiaries.

Work Incentives Planning and Assistance (WIPA)

Outside of our agency, the WIPA cooperative agreement program assists disability beneficiaries across the country. WIPA grantees are community-based organizations such as Centers for Independent Living, Goodwill, State agencies, United Cerebral Palsy, and a host of non-profit organizations that help disability beneficiaries understand work incentives and their effect on disability benefits. They employ Community Work Incentive Coordinators who are work incentive experts. Given the complexity of our work incentives, providing this assistance is of vital importance and is the WIPA program’s greatest strength.

We need to build on this strength. Based on our experience, we are adopting a strategy that focuses on showing beneficiaries what it would be like to obtain and sustain financial independence. As a part of this strategy, we want our WIPA grantees to provide information and coaching on the steps our disability beneficiaries must take to achieve financial independence, including building savings and assets. We will also identify the outcomes we want the WIPA program to achieve, and we will hold our grantees responsible for achieving them.

Protection and Advocacy for Beneficiaries of Social Security (PABSS)

The PABSS is a network of organizations (State-designated Protection and Advocacy agencies) in all 50 States, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, and the tribal entities. This network represents the Nation’s largest provider of legal-based advocacy services for persons with disabilities. While WIPA grantees provide our beneficiaries with information about our work incentives, the 57 agencies in the PABSS advise beneficiaries about obtaining vocational rehabilitation and employment services. They provide advocacy and services beneficiaries may need to secure, maintain, or return to gainful employment.

Expiring Grant Authority

The Ticket Act initially authorized appropriations for WIPA and PABSS grants for each fiscal year through FY 2004. Congress subsequently passed several funding extensions. The last extension authorized funding through the end of the current fiscal year. Unless we receive reauthorization, the money for the WIPA and PABSS programs will effectively run out on June 30, 2012 and September 29, 2012, respectively. Disseminating accurate information to beneficiaries with disabilities about work incentive programs in support of return-to-work efforts is critical and we will work with Congress to improve the effectiveness of the program. We are aware of a few concerns regarding the current structure of WIPA grants. With the most recent evaluation of WIPA forthcoming shortly, we look forward to reviewing new findings on WIPA activities and working with Congress to ensure the best approach going forward.

Disability Demonstration Projects

The Ticket Act authorized us to test how certain statutory changes to the disability program would affect beneficiary work activity. Pursuant to this authority, we initiated four demonstration projects—the Benefit Offset National Demonstration (BOND), the Mental Health Treatment Study (MHTS), the Accelerated Benefits Demonstration (AB), and the Youth Transition Demonstration (YTD). Each project has distinct objectives.

Benefit Offset National Demonstration

Because SSDI beneficiaries lose all of their cash benefits for any month in which they engage in SGA after completing the trial work period, they are often reluctant to attempt to work. The BOND project tests the effects of replacing this “cash cliff” with a benefit offset that reduces SSDI benefits $1 for every $2 a beneficiary earns above the SGA threshold. This benefit offset takes effect after the beneficiary completes twelve months of work at SGA. We also offer certain BOND participants enhanced work incentives counseling. Based on data from this project, we will estimate the effect of the benefit offset and counseling on beneficiary work activity.

We began full implementation of BOND in April 2011. Enrollment will continue until September 2012. We will publish several interim reports and expect to publish a final report in late 2017.

Mental Health Treatment Study

We awarded a contract in September 2005 for the Mental Health Treatment Study. This study tested the hypothesis that access to medical care and employment supports would enable SSDI beneficiaries with schizophrenia or affective disorders to return to work. Conducted between November 2006 and July 2010, the test included 2,238 beneficiaries in 23 study sites throughout the United States. Beneficiaries volunteering to participate in the study received a random assignment to either a treatment group or a control group, and participated for 24 months. The study collected data on the primary outcome measures of employment (including earnings), health status, and quality of life. The contractor completed the final report in August 2011.

Overall, study findings show that beneficiaries in the treatment group ended the study with significantly better employment rates, better mental health, and a higher quality of life than the control group. Further, they ended the study with other better outcomes than the control group, including higher earnings and income, more hours worked, a greater number of months worked, and greater satisfaction with their main job. Thus, the treatment package succeeded in getting a large portion of beneficiaries into jobs—the primary goal of participation.

We will post the final report within the next two months on our website: http://socialsecurity.gov/disabilityresearch/mentalhealth.htm.

Accelerated Benefits Demonstration

Under current rules, most SSDI beneficiaries have a 24-month waiting period after the date of entitlement before they are eligible for Medicare. In this project, we tested the effect of providing immediate healthcare to newly entitled SSDI beneficiaries. Specifically, we tested whether providing medical benefits sooner would result in better health and return to work outcomes for beneficiaries. The project started in October 2007. We enrolled about 2,000 beneficiaries in one of three study groups: a control group, a group that receives a medical benefits package (AB group), and a group that receives the medical benefits package and comprehensive support services (AB plus group). We completed this project in December 2010. The final report is available to the public on our website: http://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/accelerated.htm.

Our major findings include:

Participants made extensive use of program services.

AB health care benefits increased health care use and reduced reported unmet medical needs.

AB Plus services encouraged people to look for work but did not increase employment levels in the first year.

AB health care benefits reduced difficulties paying for basic necessities.

We will continue to track outcomes to assess whether there are long-term employment gains and reduced need for health care that result in future savings for the Federal government.

Youth Transition Demonstration

The YTD seeks to identify effective and efficient methods for assisting youths to transition from school to work and become self-sufficient. This project identifies services, implements service interventions, and tests modified SSI income and resource exclusions that lead to better education and employment outcomes for youth with disabilities. The YTD serves youths between the ages of 14 and 25 who receive SSI or SSDI (including child's insurance benefits based on disability) or who are at heightened risk of becoming eligible for those benefits. This study will produce the first empirical evaluation of the effects of enhanced youth transition programs and modified SSI work incentives on disabled youth.

Early results from three of the YTD projects show that after 12 months, treatment youth are receiving more employment-promoting services than the control group, are more likely to have received benefits counseling, and are more likely to use certain SSA work incentives.

Several interim reports are available to the public on our website: http://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/youth.htm. We plan to complete a comprehensive final report on this project by 2014.

Promoting Readiness of Minors in SSI

The FY 2012 President’s Budget includes a pilot project called Promoting Readiness of Minors in SSI (PROMISE), which would focus on young people with disabilities who receive SSI and help them to transition into the workforce. We expect PROMISE to help us further promote financial independence among our younger disability beneficiaries.

Conclusion

We are firmly committed to assisting beneficiaries with disabilities who want to return to work and become self-supporting. With the revisions to the Ticket regulations in 2008 and expanded outreach activities, the Ticket program is on the right track. However, we still must simplify our work incentive programs and refocus our strategy to promote the idea of financial independence more vigorously.

With the changes I discussed, our return to work programs will better nurture, encourage, and support disability beneficiaries. More of them could earn their way off cash benefits in order to live a better life and create a more secure future for themselves and their families.

Thank you again for your support and interest in this matter.