Deputy Commissioner

Office of Disability Adjudication and Review

Social Security Administration

before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

Subcommittee on Energy Policy, Health Care, and Entitlements

November 19, 2013

Chairman Lankford, Ranking Member Speier, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I appreciate the opportunity to discuss our management of the disability appeals process. Today, I will share with you our important progress in modernizing the process and improving the quality of our hearing decisions and how we are addressing some of our challenges. Before doing so, I will briefly discuss the vital programs that the Social Security Administration (SSA) administers.

Introduction

We administer the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, commonly referred to as "Social Security," which protects against loss of earnings due to retirement, death, and disability. Social Security provides a financial safety net for millions of Americans-few programs touch as many Americans. We also administer the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, funded by general revenues, which provides cash assistance to persons who are aged, blind, and disabled, as defined in the Social Security context, with very limited means.

We also handle lesser-known but critical services that bring millions of people to our field offices or prompt them to call us each year. For example, we issue replacement Medicare cards and help administer the Medicare low-income subsidy program.

Accordingly, the responsibilities with which we have been entrusted are immense in scope. To illustrate, in fiscal year (FY) 2012 we:

- Paid over $800 billion to almost 65 million beneficiaries;

- Handled over 56 million transactions on our Nation al 800 Number Network;

- Received over 65 million calls to field offices nationwide;

- Served about 45 million visitors in over 1,200 field offices nationwide;

- Completed over 8 million claims for benefits and 820,000 hearing dispositions;

- Handled almost 25 million changes to beneficiary records;

- Issued about 17 million new and replacement Social Security cards;

- Posted over 245 million wage reports;

- Handled over 15,000 disability cases in Federal District Courts;

- Completed over 443,000 full medical continuing disabili ty reviews (CDR); and

- Completed over 2.6 million non-medical redeterminations ofSSI eligibility.

When the American people turn to us for any ofthese vital services, they expect us to deliver a quality product. Our employees take pride in delivering caring, effective service. The aging of the baby boomers, the economic downturns, additional workloads like the growing demand for verifications for other programs, and tight budgets increase our challenges to deliver.

Program Integrity Work

Further, while outside my direct seope in the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review, as Acting Commissioner Carolyn Colvin has explained, budgets have also affected our ability to conduct vital program integrity work, which helps ensure that only those persons eligible for benefits continue to receive them. There is a long-standing adage in our agency-the right check to the right person at the right time. Delivering on this statement is our goal because we know that when we accomplish it we are demonstrating our stewardship and preserving the public's trust in our programs. Although we estimate that we save the Federal government $9 per dollar spent on continuing disability reviews (CDRs), we have a backlog of 1.3 million CDRs because we have not received annual appropriations that would allow us to conduct all of our scheduled CDRs.

The FY 2014 President's Budget includes a legislative proposal that would provide a dependable source of mandatory funding to significantly ramp up our program integrity work.1 In FY 2014, the proposal would provide $1.227 billion, allowing us to process hundreds of thousands more CDRs.2

The Disability Insurance (DI) program

Before discussing the improvements we have made to the disability appeals process, I would like to highlight a few aspects of the Disability Insurance (DI) program.

- First, Congress established a strict standard of disability for our disability programs. For example, the DI program does not provide short-term or partial disability benefits. Instead, an insured claimant is eligible only if he or she cannot engage in any substantial work because of a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that has lasted or is expected to last at least one year or to result in death.

A claimant cannot receive disability benefits simply by alleging the existence of pain or a severe impairment. We require objective medical evidence and laboratory findings that show the claimant has a medical impairment that: 1) could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged, and 2) meets our disability requirements when considered with all other evidence.

- In December 2012, a worker who was found to be disabled in the Social Security context received, on average, a little over $1,100 in SSDI benefits per month, barely above the current poverty income level of $13,000 per year.

- Recently, there has been some growth in the DI program. Our Chief Actuary has explained that long-term DI program growth was predicted many years ago and is driven, for example, by the aging of the baby boom generation and the fact that more women have joined the labor force and have become eligible for benefits.

Improving Public Service: Quality, Timeliness, and Oversight

Had we had this conversation about the hearings operation in 2007, the topic would likely have been, as it was at the time, the unconscionable service we were delivering to your constituents. The average wait for a person to receive a hearing decision was over 500 days. Over 63,000 people waited over 1,000 days for a hearing. Some people waited as long as 1,400 days. Congress made it clear that addressing untimely hearing decisions must be our top priority.

In developing efficient and effective solutions to the hearing delays, we implemented a comprehensive operational plan to better manage our unprecedented workload. This plan addressed the many issues we must balance in the hearing process - quality, accountability, and timeliness. We made dozens of significant changes, including increasing the number of ALJs and support staff, increasing the number of hearing offices, establishing national hearing centers, expanding video conferenc ing to conduct hearings, improving information technology, and standardizing business processes, to name just a few. Congress provided additional resources, which were critical to supporting our improvements.

Today, the results are clear that our plan has worked. We have significantly improved the quality and timeliness of our hearing decisions. We steadily reduced the wait for a hearing decision from a high of 512 days in fiscal year (FY) 2007, to 375 days in FY 2013. While this number is still too high and is increasing under budget cuts, it is still a dramatic improvement from 2007.

We have made tremendous improvement in our service to the public by focusing on our most aged cases. We have decided nearly a million aged cases since FY 2007, and today we have virtually no hearing requests over 700 days old, with the vast majority of our cases falling between 100 to 400 days old.

Our improvements include modernizing our information technology infrastructure in the hearing operation. Not that long ago, we were an entirely paper-based organization. We lost precious time and flexibility mailing huge paper cases through each step of our disability process. Now, we are nearly entirely electronic, allowing us to more efficiently help Americans. We conduct over 150,000 video hearings annually, and the Administrative Conference of the United States (ACUS) has cited SSA's video hearings process as a best practice for all Federal agencies. Going electronic means that we have data available that we have never had before and we are using these data to inform our policies and improve quality. Not only do we work in a fully electronic processing environment, but many claimants and third parties interact with us electronically as well.

We have improved the training we provide to our ALJs to help ensure that our hearings and decisions are consistent with the law, regulations, rulings, and agency policy. Since FY 2007, our new ALJs have undergone rigorous selection and have participated in a two-week orientation, four-week in-person training, formal mentoring, and supplemental in-person training. We provide ALJs with easy access to information on the reasons for their Appeals Council remands and other data through an electronic tool. Because we can now gather and analyze common adjudication errors, we provide quarterly continuing education training to all adjudicators that targets these common errors. In addition, we have continued our training program that provides in-person technical training for 350 of our ALJs each year.

As a result, quality is improving. This improvement is not happenstance but the result of these deliberate changes we have made in the way we hire, to the way we train, to the way we give feedback. For denial decisions, we have seen ever-increasing concordance between ALJ decisions and the Appeals Council. We now have increasing amounts of data to detect areas of policy non-compliance on allowances, and we are using that data to provide better feedback to adjudicators to improve policy compliance.

This improved quality means that the Appeals Council is remanding fewer cases to our ALJs for possible corrective action. The percentage of cases appealed to Federal court is also decreasing. While management is providing the support for adjudicators that leads to these results, it is the adjudicators themselves who have responded positively to the feedback. Perhaps for the first time, we have a feedback loop that allows adjudicators to actively participate in improving their work and in telling us about disagreements or problematic areas.

We could not have realized these improvements without the dedication of our ALJ corps and all of our employees. I thank them for their hard work.

Despite the tremendous advancement we have made, I am concerned that our improvements will erode. The number of hearing requests we receive each year remains high, and we are losing many ALJs and support staff due to attrition, whom we are unable to replace. We are doing what we can to hold steady on our progress despite the loss of employees. However, our progress has slowed in the last year, and we were unable to open eight new hear ing offices planned for Alabama, California, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New York, and Texas.

Ensuring High Quality, Policy Compliant, and Legally Sufficient Decisions

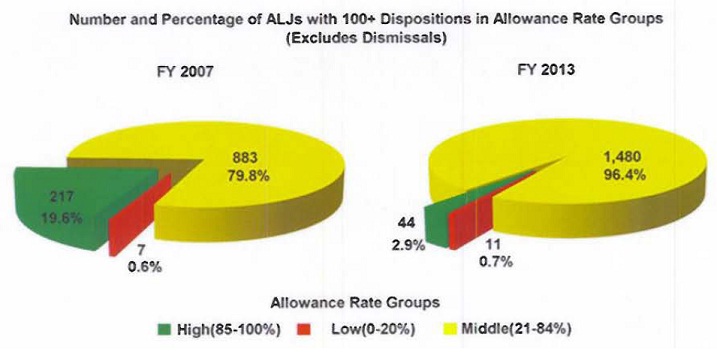

Over the past several decades, we have been accused of sacrificing quality by reflexively denying too many disability claims or by granting them too readily. These reports ignore the reality that we are making quicker, higher quality disability decisions. Over the past six years, the allowance and denial rates have become more consistent throughout the ALJ corps, reflecting an emphasis on quality decision making. There are now significantly fewer ALJs who allow more than 85 percent of their cases than there were in FY 2007. Meanwhile, there is less than one percent of the ALJ corps that pays fewer than 20 percent of their cases.

Let me categorically state that we have no targets or goals regarding these rates. We are focused on delivering policy compliant decisions. In that regard, an ALJ with a very high or a very low allowance rate may raise a quality red flag. However, we have to look behind the data to see the cause. With our automation efforts, we now have a process and the data to do so.

Figure 1: ALJ Allowance Rate Groups

The quality of our benefit decisions is a paramount concern for the agency. We took aggressive steps to institute a more balanced quality review in the hearings process. Our first effort in this area was to develop serious data collection and management information for the Office of Disabil ity Adjudication and Review (ODAR). We then revived development of an electronic policy-compliance system for the Appeals Council (AC). Because the Office of Appellate Operations (OAO) handles the final level of administrative review, it has a unique vantage point to give feedback to decision and policy makers. OAO developed a technological approach to harness the wealth of information the AC collects, turning it into actionable data. These new tools permitted the OAO to capture a significant amount of structured data concerning the application of agency policy in hearing decisions.

Using these data sets, we provide feedback on decisional quality, giving adjudicators real-time access to their remand data. We are creating better tools to provide individual feedback for our adjudicators. One such feedback tool is "How MI Doing?" This resource not only gives ALJs information about their AC remands, including the reasons for remand, but also information on their performance in relation to other ALJs in their office, their region, and the nation. Currently, we are developing training modules related to each of the 170 identified reasons for remand that we will link to the "How MI Doing?" tool. ALJs will be able to receive immediate training at their desks that is targeted to the specific reasons for the remand. We develop and deliver specific training that focuses on the most error-prone issues that our judges must address in their decisions. Data driven feedback informs business process changes that reduce inconsistencies and inefficiencies, and simplify rules.

In FY 2010, OAO created the Division of Quality (DQ) to focus specifically on improving the quality of our disability process. While AC remands provide a quality measure on ALJ denials, prior to the creation of DQ, we did not have the resources to look at ALI allowances. Since FY 20II, DQ has been conducting pre-effectuation reviews on a random sample of ALJ allowances. Federal regulations require that preeffectuation reviews of ALJ decisions must be selected at random or, if selective sampling is used, may not be based on the identity of any specific adjudicator or hearing office. Currently, DQ reviews a statistically valid sample of un-appealed favorable ALJ hearing decisions.

DQ also performs post-effectuation focused reviews looking at specific issues. Subjects of a focused review may be hearing offices, ALJs, representatives, doctors, and other participants in the hearing process. The same regulatory requirements regarding random and selective sampling do not apply to post-effectuation focused reviews. Because these reviews occur after the 60-day period a claimant has to appeal the ALJ decision , they do not result in a change to the decision.

The data collected from these quality initiat ives identify for us the most error-prone provisions of law and regulation, and we use this information to design and implement our AU training efforts. To ensure that all of our ALJs comply with law, regulations, and policies, we provide considerable training including both new and supplemental ALJ training. We train our ALJs on the agency's rules and policies, and that training is vetted thoroughly by various components, including the component that is responsible for disability policy. For the past several years, our new AU training also has included a session that explains the scope and limits ofan ALJ's authority in the hearing process, including the ALJ's obligation to follow the agency's rules and policies. We also have implemented the ALJ Mentor Program, which pairs a new ALJ with an experienced ALJ, who provides advice, coaching, and expertise. Additionally, we provide regular guidance to ALJs through Chief Judge Memoranda and bulletins, Interactive Video Teletraining sessions, and in responses to specific queries from the field.

Additional efforts to promote policy compliance include a pilot of the Electronic Bench Book (eBB) for our adjudicators. The eBB is a policy-compliant web-based tool that aids in documenting, analyzing, and adjudicating a disability case in accordance with our regulations. We designed this electronic tool to improve accuracy and consistency in the disability evaluation process.

These efforts are testing some longstanding traditions within ODAR. We are moving from training based primarily on anecdotal information as to our most significant problems to a data-driven identification of training, guidance, and policy gaps. We now develop training materials and automated tools designed to improve both the adjudicator's efficiency and accuracy in case adjudication. We are transparent with the information that we are collecting so that the ALJs can more readily make use of the information.

In addition, the data collected by DQ provide us with a tremendous tool to identify trends. We review our electronic records for anomalies; when we find them, we look to identify whether such anomalies can be explained or whether administrative action is appropriate. When we suspect fraud or other suspicious behavior, we refer the matter to our Office of Inspector General.

These new quality initiatives have given us a new opportunity to improve our policy guidance. We are using these data to help us identify and pursue regulatory and policy changes to improve our disability process. However, there are many stakeholders on both sides of any policy that affects our disability programs. To objectively address concerns about changes to various aspects of our disability programs, we have contracted with the ACUS to review several issues for us. ACUS has looked at challenging and potentially controversial issues that affect the hearings process , including the submission of evidence and duty of candor, the treating source rule, closing the record, and video hearings. We are moving forward on many of these issues, but gathering objective evidence and considering input from all stakeholders takes time.

Ensuring Timely Decisions

Timeliness is one aspect of quality from a claimant's perspective. No elaimant would say that waiting 1,400 days or 1,000 days or even 400 days to know the outcome of their claim is quality service.

As part of our efforts to ensure hearing decisions are legally sufficient and time ly, we have given ALJs a range of 500-700 decisions a year as a reasonable expectation based on what many ALJs were already doing. We have never required an ALJ to do 500-700 cases per year. These judges receive lifetime appointments. They know when accepting the job that we will expect them to be able to deliver a policy compliant decision in a production environment. The public has every right to expect them to work hard, and most judges meet that expectation. We are responsible for providing them with the framework for success. For example, each ALJ has between four and five staff members who directly contribute to a disposition.

Our previous Chief ALJ established this expectation after consulting with a number of managers and ALJs about the reasonableness of the expectation . The range of 500 to 700 dispositions was consistent with a prior goal set in 1981. At that time, the agency asked ALJs to complete 45 dispositions a month or 540 a year. With significant advances in technology over the last 26 years and increasing the number of support staff for ALJs, it was not surprising that when the agency articulated the 500-700 expectation, almost 50 percent of ALJs were issuing at least 500 dispositions a year. From the start, the 500 to 700 expectation was not a quota and was not a mandate. In FY 2012, approximately 78 percent of our ALJs met the expectation.

I want to be very clear that I expect all dispositions to be not just timely but legally sufficient, and we are demonstrating that we are serious about quality with our investments.

Moreover, in a survey conducted Iast year by the Association of Administrative Law Judges, nearly three out of four respondents found it "not difficult at all" or only "somewhat difficult" to meet the expectation. When given an opportunity to explain why they had not met the agency's expectation, many respondents cited their status as new ALJs. In fact, we account for the learning curve for new ALJs. We reiterate the importance of making the right decision and we do not ask our newly-hired ALJs to meet the full workload expectation during their first year learning the job.

When an ALJ has workflow issues, we work with the ALJ on an informal basis to resolve those issues and to assist the ALJ.

If issues cannot be remedied informally, then we take affirmative, and typically progressive, steps to address problems, including counseling, training, mentoring and, as a last resort, adverse action pursuant to 5 U.S.C. 7521. With the promulgation of our "time and place" regulation, we have eliminated ambiguities regarding our authority to manage scheduling, and we have taken steps to ensure that ALJs are deciding neither too few nor too many cases. By management instruction, we are limiting assignment of new cases to no more than 840 cases annually.

ALJ Management Oversight

ALJs have qualified decisional independence. That qualified decisional independence allows ALJs to issue decisions consistent with the law and agency policy, rather than decisions influenced by pressure to reach a particular result. The primary purpose of an ALJ's qualified decisional independence is to enhance public confidence in the essential fairness of an agency's adjudicatory process. We fully support Congress' intent to ensure the integrity ofthe hearings process, and we note that the Supreme Court has recognized that Congress modeled the Administrative Procedure Act after our hearings process.

The mission of our hearing operation is to provide timely and legally sufficient hearings and decisions. For our hearing process to operate efficiently and effectively, we need ALJs to treat members of the public and staff with dignity and respect, to be proficient at working electronically, and to be able to handle a high-volume workload in order to makeswift and sound decisions in a non-advcrsarial adjudication setting. Let me emphasize that the vast majority of the ALJs hearing Social Security appeals do an admirable job. They handle the complex cases in a timely manner, while conforming to the highest standards of conduct and quality.

The law has guided our path to holding our judges accountable. In 2006, the agency began to seriously examine the scope ofdecisional independence and test our management authority. Since FY 2007, we have been working diligently to improve management oversight of our ALJs to ensure that they adhere to policies, regulations, and laws, while maintaining the ALJs' qualified decisional independence. We expect our ALJs to adhere to the high standards expected ofthem, recognizing at the same time that we cannot and would not influence their decision in any particular case. Through the actions the agency brought to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), we confirmed, among other issues, that when management addresses case processing, including discipline for purposeful failure to follow policy, it does not interfere with an ALJ's qualified decisional independence. We also confirmed that ALJs must adhere to the same standards of conduct as other federal employees. Over 20 ALJs have separated from the agency through tinal MSPB decisions or resolution agreements. Nearly all of these cases have involved serious conduct issues.

Disciplinary Action

Again, I must emphasize that the vast majority of our ALJs arc conscientious and hardworking employees who take thei r responsibility to the public very seriously. For these ALJs, we can rely on current agency measures including training to address any problems they may have. Generally, the informal process works, but when it does not, management has the authority to order an AU to take a certain case processing action or explain why he or she cannot take such case processing actions. ALJs rarely fail to comply with these orders. In those rare cases where the ALJ does not comply and where appropriate, we pursue disciplinary action.

However, when ALJ performance or conduct issues arise, agencies such as SSA are more limited in the manner in which they can attempt to correct the issues. For example, agency managers may take certain corrective measures, such as informal counseling or issuing a disciplinary reprimand. However, the agency cannot take stronger disciplinary measures against an ALJ, such as removal or suspension, reduction in grade or pay, or furlough for 30 days or less, unless the MSPB finds that good cause exists.

The current system makes it challenging to address the tiny fraction of ALJs who hear or decide only a handful of cases, fail to decide cases in a legally sufficient manner, allow cases under their control to languish, or otherwise engage in misconduct. A few years ago, we had an ALJ who failed to inform us, as required, that he was also working fulltime for the Department of Defense. Another ALJ was arrested for committing a serious domestic assault. More recently, an ALJ failed to follow his managers' orders to process his cases. We removed these ALJs, but only after completing the lengthy MSPB disciplinary process that lasts several years and can consume over a million dollars of taxpayer resources. In each of these cases, unlike disciplinary action against all other civil servants, the law required that ALJs receive their full salary and benefits until the case was finally decided by the full MSPB---even though the agency could not allow them in good conscience to continue deciding and hearing cases. We remain open to exploring different options to address this matter, while ensuring the qualified decisional independence of ALJs.

Conclusion

Over fifty years ago, Congress created the disability program to help some of our most vulnerable citizens. The vast majority of our adjudicators care very much about making the right decision and being good stewards of the tru st funds, and we are committed to helping them do their jobs effectively.

We thank you for your interest in helping us improve our service and ensure ongoing confidence in our programs. We also ask for your support for the President's budget request, which will provide us with funding to continue to improve our hearings process, to improve the integrity of our disability programs, and to reduce improper payments. With past support from Congress, we have made progress in both the administrative and program integrity arenas and we all benefit if that progress is not lost.

Again, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I will do my best to answer any questions you may have.

______________________________________________

1 These mandatory funds would replace the discretionary cap adjustments authorized by the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended by the Budget Control Act. These funds would be reflected in a new account, the Program Integrity Administrative Expenses account, which would be separate, and in addition to, our Limitation on Administrative Expenses (LAE) account. Under the proposal, the funds would be available for two years, providing us with the flexibility to aggressively hire and train staff to support the processing of more program integrity work.

2 With this increased level of funding, the associated volume of medical CDRs is 1.047 million, although it may take us some time to reach that level. For comparison, we conducted about 430,000 CDRs in FY 2013.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Statement of Judge Jasper J. Bede,

Regional Chief Administrative Law Judge

Social Security Administration

before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

Subcommittee on Energy Policy, Health Care, and Entitlements

November 19, 2013

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Speier, and Members of the Subconunittee:

My name is Jasper J. Bede, and I serve as the Chief Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) for Region III (Philadelphia). I have held this position with the Social Security Administration (SSA) since April 2006. I was the Hearing Office Chief ALJ (HOCALJ) in the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania Hearing Office from 2002 to 2006. I was appointed to the position of ALJ in 1991, after working at SSA as an Appeals Officer, Supervisory Attorney Advisor and Attorney Advisor. Prior to my employment with SSA, I was an Officer in the United States Army.

Region III includes Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. The population we serve is a reflection of the wider population of the United States from farm laborers and coalminers to medical researchers and software designers. Many of the claimants who appear before our judges have unskilled work backgrounds and less than a high school education, but we also see claimants who have achieved the highest levels of education and worked in the most skilled professions.

Region III has 18 Hearing Offices, 150 ALJs, and approximately 742 support staff. Currently, Region III has 98,213 cases pending, and in fiscal year 2013, we closed 80,753 cases with an average processing time of 407 days. Region III ranks first in the nation in quality measures with an 87.7 percent Appeals Council agree rate. We also have the first and second ranked Hearing Offices in the nation (Johnstown and Seven Fields).

As the Chief ALJ in Region III, my job is to make sure our offices best serve our claimants and contribute to ODAR's mission of providing timely and quality service to the public. I frequently visit the hearing offices in my region and emphasize our goals of providing timely, policy-compliant decisions. I set up one-on-one meetings with all of the new ALJs in my region, and I make myself available to all staff. With regard to ALJs, if I learn of an issue, I work with the Hearing Office Chief ALJ to discuss the issue and to assist the ALJ. If informal discussions with the ALJ do not correct the problem, I may counsel the ALJ or issue a formal reprimand. For more serious issues, I can request that the Chief ALJ initiate proceedings with the Merit Systems Protection Board.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I would be happy to answer any questions that you may have.