Office of Appellate Operations

Office of Disability Adjudication and Review

Social Security Administration

before the Senate Committee on

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

September 13, 2012

Chairman Levin, Ranking Member Coburn, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today. My name is Judge Patricia Jonas. I am the Executive Director of the Office of Appellate Operations and the Deputy Chair of the Appeals Council (AC) at the Social Security Administration Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR). Since 1940, the AC has operated under a direct delegation of authority from the Commissioner of Social Security to help oversee the hearings process. The AC conducts reviews of practices and decisions based on this authority. I oversee approximately 75 administrative appeals judges of the AC who review both the allowances and denials made by our administrative law judges (ALJ).

I understand the Subcommittee is preparing to release a report concerning 300 disability cases—100 each from Buchanan County, VA, Dallas County, AL, and Oklahoma County, OK. We have not yet seen that report, but we look forward to reviewing it and working with the Subcommittee to collect meaningful data about areas of mutual concern. We recognize that the conclusions of this study will be severely limited by the statistically non-representative sample of cases that was studied. That said, we are hopeful that the report will identify data that merit further research. We are also pleased to share with you the agency’s preliminary findings from its separate review of the 300 cases.

In addition to addressing the findings from your report, I want to take this opportunity to update you on the improvements we have made to the hearings and appeals process. The Supreme Court has recognized that we are “probably the largest adjudicative agency in the western world,” and we take very seriously our responsibility to issue timely and accurate decisions.1

When Commissioner Astrue arrived five years ago, there was widespread discontent with backlogs and delays in the disability system. There was also significant concern about the quality of our decision-making. The majority of a prior agency plan to fix those problems—Disability Service Improvement (DSI)—was halted so that resources could be redirected to backlog reduction. The numbers tell the story. At the time, over 63,000 people waited over 1,000 days for a hearing, and some people waited as long as 1,400 days. We were failing the public.

Right from the beginning, Commissioner Astrue’s refrain was that we could not take the easy road of short-term fixes on backlogs that would aggravate our quality issues. With that principle in mind, Commissioner Astrue developed an operational plan that focused on the gritty work of truly managing the unprecedented hearings workload. We made dozens of incremental changes, including using video more widely, improving information technology, simplifying regulations, standardizing business processes, and establishing ALJ productivity expectations, to name just a few. Additional resources provided by Congress in the Recovery Act were critical to supporting these initiatives.

Today, the result is clear—the plan has worked. Average processing time, which stood at 532 days in August 2008, steadily declined for more than three years, and currently stands at 359 days.

This improvement in our ability to hold hearings and issue timely decisions is even more impressive when you consider that we have given priority to the oldest cases, which are generally the most complex and time-consuming. Since 2007, we have decided over 600,000 of the oldest cases. Each year, we lower the threshold for aged cases to ensure that we continue to eliminate the oldest cases first. We ended fiscal year (FY) 2011 with virtually no cases over 775 days old. Through the steady efforts of our employees, we now define an aged case as one that is 725 days or older, and we have already completed over 90 percent of them. Next year, our management goal is to raise the bar on ourselves again by focusing on completing all cases over 675 days old.

As we have worked to provide your constituents with quicker decisions, we have not forgotten our duty to ensure that every decision is fair and meets the requirements of the law. In short, we strive to make sure that our decisions are of the highest quality.

Prior to Commissioner Astrue’s arrival, due to several years of budget shortfalls, the agency had performed very little quality review at ODAR, in large part due to litigation and congressional reaction to the “Bellmon Review” in the 1980s. And perhaps equally important, as a result of that litigation and congressional reaction, our policy guidance and feedback to our ALJs was limited. For many years, a remand order was the primary method of providing written feedback from the AC to ALJs. While this method of providing feedback and guidance to ALJs is still an appropriate mechanism when addressing individual cases, there are limitations. For example, the number of remands to any ALJ is relatively small, and, until the reintroduction of a favorable review effort at the AC, the feedback was generally limited to cases in which the ALJ made an unfavorable decision.

However, under Commissioner Astrue’s leadership, we took aggressive steps to institute a more balanced quality review into the hearings process. The first step was to develop serious data collection and management information for ODAR, and the next step was to revive development of an electronic policy-compliant system for the AC, which had been terminated by the DSI initiative. These new tools permitted the AC to capture a significant amount of structured data concerning the application of agency policy in hearing decisions. In December 2008, Commissioner Astrue provided resources to our Office of Quality Performance to institute an independent national-level review of hearings level decisions to ensure a consistent and comparative review for all three adjudicative levels of the agency’s disability process. Also, in 2009, Commissioner Astrue reestablished the quality review function in the AC, known as the Division of Quality (DQ), that reintroduced review of a sampling of favorable hearing decisions. This office took about a year to implement fully since we had to hire, train,and lease office space for about 50 staff whose function is to identify quality issues in the processing of disability cases at the hearings level. Beginning in September 2010, the DQ began to conduct the reviews of favorable hearings level decisions.

These new quality initiatives have given us a new opportunity to improve our feedback and policy guidance. The data collected from these quality initiatives identify the most error-prone provisions of law and regulation and this information is used to design and implement our ALJ training efforts, including the annual judicial training and mandatory quarterly training for all ALJs. We have also recently implemented a new process that expands the opportunity for ALJs to provide feedback to the AC when a remand is issued.

We also provide feedback on decisional quality, giving adjudicators real-time access to their remand data. We develop and deliver specific training that focuses on the most error-prone issues that our judges must address in their decisions. In addition, we make available specific training to address individualized training needs.

These efforts are testing some longstanding traditions within ODAR. We are moving from training based primarily on anecdotal information as to our most significant problems to a data-based identification of issues. Training materials are developed so that they are not only a policy reminder, but a skill-based training designed to improve both the adjudicator’s efficiency and accuracy in case adjudication. We are transparent with the information that we are collecting so that the ALJs can more readily make use of the information. Providing a mechanism for the ALJs to question the AC about a remand is also a new innovation. We believe that our hearings process is improving because of this increased feedback and communication.

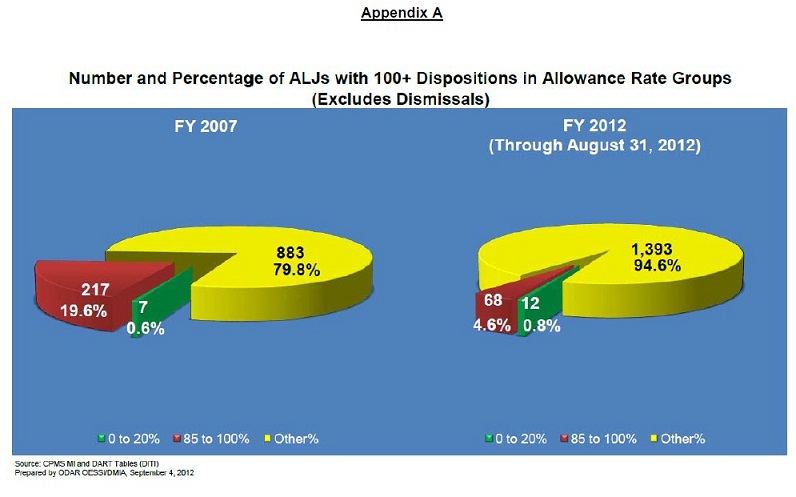

As you are aware, there is a public dialogue about our ALJs and our hearing process. Certainly, the fact that better ALJ data are readily available is a factor. Allegations both of “paying down the backlog” and fraud in the disability system have appeared in the media from time to time. These allegations are based mostly on anecdote and innuendo, and unfairly diminish our accomplishments over the past five years. Moreover, these reports often ignore the reality that we are making quicker, higher quality disability decisions. Over the past five years, the allowance and denial rates have become more consistent throughout the ALJ corps. Since FY 2007, there has been more than a two-thirds reduction in the number of judges who allow more than 85 percent of their cases.2

Of course, opportunities for continued improvement remain. Due to challenges maintaining our staffing levels and difficulty keeping up with demand, we have begun to lose ground with respect to our average processing time these last two years. At this point, it appears all but certain that we will not meet our average processing time goal of 270 days in FY 2013; however, full funding of the President’s budget would allow us to make progress.

300 Case Study Preliminary Findings

While my office has not yet reviewed the 300 disability cases provided the Subcommittee, which consisted of a mixture of decisions from all levels of our adjudication process and were weighted toward allowances, the agency’s Office of Medical and Vocational Evaluation did a basic review of them. I understand that they found a limited number of policy issues that are consistent with what we saw when the DQ in the AC conducted a national random sample review of favorable hearings level decisions in FY 2011.

Two areas that concerned us in our AC sample results were the evaluation of medical opinion and the assessment of residual functional capacity (RFC). Using the data we collected at the AC, we provided mandatory training to all ALJs on RFC and evaluation of medical source opinion earlier this year. Just as with the cases we see at the AC, the majority of the ALJs in the cases that the Subcommittee requested appear to have complied with our policies. However, there also are examples in which ALJs were not policy compliant in evaluating the appropriate weight given to a medical source’s opinion and in assessing the claimant’s RFC. There were also several case examples from one ALJ in which the written decision appeared inaccurate and contained boilerplate information that was not relevant to the individual claimant. That same issue had been seen by the DQ in the random sample review and, as a result, the Chief ALJ had instructed the ALJ to discontinue this practice. This example shows that our improvements are producing positive results.

Building Speed and Quality into the Hearings and Appeals Process

When the agency established the hearings process in 1940, it designed the process to handle a substantial number of cases—that is, a larger number than was handled in other hearing processes.3 However, over the years, that number has grown. In FY 2007, we received nearly 580,000 hearing requests; last fiscal year, we received over 859,000 hearing requests, which was a record number. The main reason behind this workload growth in recent years has been the flood of new appeals caused by the aging of the baby boomers and the economic downturn. Rapid expansion of large firms representing claimants may also be a factor in the higher rate of appeal.

To address these growing workloads, we decided to return to the gritty work of truly managing our hearings and appeals workloads.

We hired additional ALJs for the offices with the heaviest workloads and informed our entire corps of our expectation that they should issue between 500 and 700 legally sound decisions annually.4 When we established that productivity expectation in late 2007, only 47 percent of the ALJs were achieving it. In FY 2011, 77 percent met the expectation, and we expect that percentage to rise this fiscal year.

We opened five National Hearing Centers (NHC) to further reduce hearings backlogs by increasing adjudicatory capacity and efficiency with a focus on a streamlined electronic business process. Transfer of workload from heavily backlogged hearing offices is possible with electronic files, thus allowing the NHC to easily provide assistance to these areas of the country.

In 2010 and 2011, we opened 24 new hearing offices and satellite offices. While a lack of funding forced us to cancel plans for additional offices, those we did open are making a substantial difference in communities that were experiencing the longest waits for hearings.

We increased usage of the Findings Integrated Templates that improve the legal sufficiency of hearing decisions, conserve resources, and reduce average processing time. We introduced a standard Electronic Hearing Office Process, also known as the Electronic Business Process, to promote consistency in case processing across all hearing offices. We also built the “How MI Doing” tool that gives adjudicators extensive information about the reasons their cases were subsequently remanded and allows them to view their performance in relation to the average of other ALJs in the office, region, and Nation. Currently, we are developing training modules for each of the 170 bases for remands that eventually will be linked to this tool so that ALJs can obtain training on targeted issues.

We expanded automation tools to improve speed, efficiency, quality, and accountability. We initiated the Electronic Records Express project, which provides electronic options for submitting health and school records related to disability claims. This initiative saves critical administrative resources because our employees burn fewer CDs freeing them to do other work. In addition, appointed representatives with e-Folder access have self- service access to hearing scheduling information and the current Case Processing and Management System (CPMS) claim status for their clients, reducing the need for them to contact our offices. We have registered over 9,000 representatives for direct access to the electronic folder. We also implemented Automated Noticing that allows CPMS to automatically produce appropriate notices based on stored data. We implemented centralized printing and mailing that provides high-speed, high-volume printing for all hearings and appeals offices. We implemented Electronic Signature that allows ALJs and Attorney Adjudicators to sign decisions electronically.

Additionally, we are developing another automated tool, the electronic bench book (eBB), which we believe will help ALJs review, decide, and provide instructions for decision writers in a fully electronic environment. Last month, we initiated a pilot of the eBB in three hearing offices. The eBB is a web-based tool that aids in documenting, analyzing, and adjudicating a disability case according to our regulations. Wherever possible, we reuse data to limit the need to re-enter information. eBB is designed to pull in and display information entered from various sources. eBB should make review of the electronic file and instructions to decision writers more complete and efficient, which would reduce the number of cases remanded because of incomplete documentation.

We have Federal disability units that provide extra processing capacity throughout the country. In recent years, these units have been assisting stressed State disability determination agencies. After evaluating our limited resources, our success in holding down the initial disability claims pending level, and a further spike in hearings requests, we redirected these units in February 2012 to assist in screening hearings requests. Our Federal disability units can make fully favorable allowances, if appropriate, without the need for a hearing before an ALJ.

We also listened to criticism from Congress and others. We have tried to make the right decision upfront as quickly as possible. For instance, we are successfully using our Compassionate Allowances (CAL) and Quick Disability Determination initiatives to fast- track disability determinations at the initial claims level for over 150,000 disability claimants each year, while maintaining a very high accuracy rate. Currently, about 6 percent of initial disability claims qualify for our fast-track processes, and we expect to increase that number as we add new conditions to our CAL program. This helps keep these cases out of our appeals process altogether.

At the AC, we also made improvements that helped us to handle the influx of cases from the hearing offices and improve the quality of decisions throughout our entire hearings and appeals process. For example, we developed and are now using the Appeals Review Processing System (ARPS), an Intranet case processing system that helps staff identify errors, prepare recommendations for review, identify trends, and provide feedback to adjudicators and staff.

Over the last few years, the AC has developed an interactive training model that received the prestigious W. Edwards Deming Training Award from the Graduate School USA in 2011.

In the future, we plan to implement a new case assignment model for the AC that will group cases with similar issues and assign those cases concurrently. This change will improve consistency and help identify areas for future training, while also decreasing processing times for all claimants.

However, of all the important improvements we have made or plan to make at the AC, none is more important than the recent creation of the DQ. In 2008, we presented Commissioner Astrue with a plan that would allow us to gather comprehensive data on the quality of our hearing decisions. Recognizing an obvious need, Commissioner Astrue established a workgroup in 2009, which led to the establishment of DQ in September 2010.

Even in the beginning, when the data were just trickling in, we began to identify decision-making issues that we knew needed to be addressed through rulemaking or sub-regulatory action.

Currently, DQ reviews a statistically valid sample of un-appealed favorable ALJ hearing decisions before those decisions are effectuated (i.e., finalized), as authorized by 20 CFR 404.969 and 416.1469. In FY 2011, DQ reviewed 3,692 partially and fully favorable decisions issued by ALJs and attorney adjudicators, and took action on about 22 percent, or 812, of those cases.5

While longstanding regulations do not permit our DQ to do pre-effectuation reviews that are based on a specific ALJ or hearing office, the DQ is able to conduct post- effectuation focused reviews on specific hearing offices, ALJs, representatives, doctors, and disability program issues, etc.6 These reviews allow us to better understand how our complex disability policies are being implemented by various parties throughout the hearings level. We identify potential subjects for focused reviews from a variety of sources, including data collected through our systems, findings from pre-effectuation reviews, and internal and external referrals received from various sources regarding potential non-compliance with our regulations and policies. One way we use these reviews is to identify common errors in ALJ decisions. The results of these reviews show common errors to be failure to adequately develop the record, lack of supporting rationale, and improper evaluation of opinion evidence. We have used this information to develop and implement mandatory training for our ALJs. Furthermore, we use the comprehensive data and analysis provided by DQ to provide feedback to other components on policy guidance and litigation issues.

Moreover, since we are handling more cases in both our hearing offices and at the AC, the number of new Federal court cases filed challenging our final decisions has gone up. In FY 2007, dissatisfied claimants filed 11,920 new cases. That number rose to 15,644 in FY 2011, and we project that there will be about 19,100 new cases filed in FY 2013. Our success in the courts has also improved. In FY 2011, courts affirmed our decisions in 51 percent of the cases decided, up from 49 percent in FY 2007, and court reversals have decreased from 5 percent to fewer than 3 percent of cases over this time.

Finally, notwithstanding our impressive work to-date, we have sought outside advice from the Administrative Conference of the United States (ACUS) to guide our future quality improvement efforts in our hearing offices and at the AC. Currently, ACUS is studying:

• The effect of the treating physician rule on the role of the courts in reviewing our disability decisions and the measures that we could take to reduce the number of remanded cases;

• The AC’s role in reviewing cases to reduce any observed variances and the efficacy of expanding the AC’s existing authority to conduct more focused reviews of judge decisions; and

• How the AC can select cases for review—as well as when the AC should select cases for review (i.e., pre- or post-effectuation)—and what should be the scope and manner of review.

We expect ACUS to deliver its preliminary findings by the end of this calendar year and a draft final report with recommendations early next year.

Additionally, we have also asked ACUS to review and analyze the Social Security Act and our regulations regarding the duty of candor and the submission of all evidence in disability claims. ACUS will also survey the requirements of other administrative tribunals, as well as the Federal Rules of Evidence, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and other applicable authority, regarding the duty of candor and submission of all evidence and then make recommendations for improvements in the Social Security adjudication process.

Conclusion

Contrary to popular anecdote and innuendo, we have made extraordinary gains improving the speed and quality of our hearings and appeals process over the past five years. We have done so against extraordinary obstacles, including demographic challenges, the economic downturn, and fiscal belt tightening. Resources permitting, we believe that we can continue to improve by building upon our productivity gains and the body of quality review data that we have accumulated.

Finally, I look forward to reviewing the Subcommittee’s report concerning 300 disability cases. Without having seen the report, I will do my best to answer any questions you may have today. Although the report will be severely limited by the statistically non- representative sample of cases that was studied, we are nonetheless hopeful that the report will identify possible trends that merit further research.

__________________________________________________________

1 Heckler v. Campbell, 461 U.S. 458, 461 n.2 (1983).

2 See Appendix A.

3 Basic Provisions Adopted by the Social Security Board for the Hearing and Review of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Claims, at 4 (January 1940).

4 In addition, we limit the limit the number of cases assigned per year to an ALJ.

5 In those instances, the AC either remanded the case to the hearing office for further development or issued a decision that modified the hearing decision.

6 Since these focused reviews are post-effectuation reviews, they do not change case outcomes.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Chief Administrative Law Judge

Office of DIsability Adjudication and Reviewbefore the Senate Committee on

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

September 13, 2012

Chairman Levin, Ranking Member Coburn, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today. My name is Judge Debra Bice, and I am the Chief Administrative Law Judge at the Social Security Administration. I am responsible for overseeing approximately 1,500 administrative law judges (ALJ) in the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR). My testimony will focus on the process through which we determine disability at all adjudicative levels across the agency. My testimony will also address the challenges we face hiring, managing, and disciplining our judge corps.

How We Determine Disability—The Sequential Evaluation Process

Our general process for determining disability is admittedly complicated, but it is necessarily complex to meet the requirements of the law as designed by Congress.1

We evaluate adult claimants for disability under a standardized five-step evaluation process (sequential evaluation), which we formally incorporated into our regulations in 1978. At step one, we determine whether the claimant is engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA). SGA is significant work normally done for pay or profit. The Social Security Act (Act) establishes the SGA earnings level for blind persons and requires us to establish the SGA level for other disabled persons.2 If the claimant is engaging in SGA, we deny the claim without considering medical factors.

If a claimant is not engaging in SGA, at step two, we assess the existence, severity, and duration of the claimant’s impairment (or combination of impairments). The Act requires us to consider the combined effect of all of a person's impairments, regardless of whether any one impairment is severe. Throughout the sequential evaluation, we consider all of the claimant’s physical and mental impairments singly and in combination.

If we determine that the claimant does not have a medically determinable impairment, or that the impairment or combined impairments are “not severe” because they do not significantly limit the claimant’s ability to perform basic work activities, we deny the claim at the second step. If the impairment is “severe,” we proceed to the third step.

Listing of Impairments

At the third step, we determine whether the impairment “meets” or “equals” the criteria of one of the Listing of Impairments (Listings) in our regulations.

The Listings describe for each major body system the impairments considered so severe that we can presume that they would prevent an adult from working. The Act does not require the Listings, but we have been using them in one form or another since 1955. The listed impairments are permanent, expected to result in death, or last for a specific period greater than 12 months.

Using the rulemaking process, we revise the Listings’ criteria on an ongoing basis. The Listings are a critical factor in our disability determination process, and we are committed to updating each listing at least every five years. In the last five years, we have revised five of 14 body systems in the Listings, and in FY 2013 we plan to revise two more body systems and obtain public comments on the remaining seven body systems. When updating a listing, we consider current medical literature, information from medical experts, disability adjudicator feedback, and research by organizations such as the Institute of Medicine. As we update entire body systems, we also make targeted changes to specific rules as necessary.

If the claimant has an impairment that meets or equals the criteria in the Listings, we allow the disability claim without considering the claimant’s age, education, or past work experience.

As part of our process at step three, we developed an important initiative—our Compassionate Allowances (CAL) initiative—that allows us to identify claimants who are clearly disabled because the nature of their disease or condition clearly meets the statutory standard for disability. With the help of sophisticated new information technology, we can quickly identify potential Compassionate Allowances and then swiftly make decisions. We currently recognize 165 CAL conditions, and we expect to expand the list later this year. We continue to review our CAL policy to ensure we base it on the most up-to-date medical science.

Residual Functional Capacity

A claimant who does not meet or equal a listing may still be disabled. The Act requires us to consider how a claimant’s condition affects his or her ability to perform past relevant work or, considering his or her age, education, and work experience, other work that exists in the national economy. Consequently, we assess what the claimant can still do despite physical and mental impairments—i.e., we assess his or her residual functional capacity (RFC). We use that RFC assessment in the last two steps of the sequential evaluation.

We developed a regulatory framework to assess RFC. An RFC assessment must reflect a claimant’s ability to perform work activity on a regular and continuing basis (i.e., eight hours a day for five days a week, or an equivalent work schedule). We assess the claimant’s RFC based on all of the evidence in the record, such as treatment history, objective medical evidence, and activities of daily living.

We must also consider the credibility of a claimant’s subjective complaints, such as pain. Such complaints are inherently difficult to assess. Under our regulations, disability adjudicators use a two-step process to evaluate credibility. First, the adjudicator must determine whether medical signs and laboratory findings show that the claimant has a medically determinable impairment that could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged. If the claimant has such an impairment, the adjudicator must then consider all of the medical and non-medical evidence to determine the credibility of the claimant’s statements about the intensity, persistence, and limiting effects of symptoms. The adjudicator cannot disregard the claimant’s statements about his or her symptoms simply because the objective medical evidence alone does not fully support them.

The courts have influenced our rules about assessing a claimant’s disability. For example, when we assess the severity of a claimant’s medical condition, we historically have given greater weight to the opinion of the physician or psychologist who treated that claimant. While the courts generally agreed that adjudicators should give special weight to treating source opinions, the courts formulated different rules about how adjudicators should evaluate treating source opinions. In 1991, we issued regulations that explain how we evaluate treating source opinions.3 However, the courts have continued to interpret opinions from treating physicians in conflicting ways.

Once we assess the claimant’s RFC, we move to the fourth step of the sequential evaluation.

Medical-Vocational Decisions (Steps Four and Five)

At step four, we consider whether the claimant’s RFC prevents the claimant from performing any past relevant work. If the claimant can perform his or her past relevant work, we deny the disability claim.

If the claimant cannot perform past relevant work (or if the claimant did not have any past relevant work), we move to the fifth step of the sequential evaluation. At step five, we determine whether the claimant, given his or her RFC, age, education, and work experience, can do other work that exists in the national economy. If a claimant cannot perform other work, we will find that the claimant is disabled.

We use detailed vocational rules to minimize subjectivity and promote national consistency in determining whether a claimant can perform other work that exists in the national economy. When we issued these rules in 1978, we noted that the Committee on Ways and Means, in its report accompanying the Social Security Amendments of 1967, said that:

It is, and has been, the intent of the statute to provide a definition of disability which can be applied with uniformity and consistency throughout the nation, without regard to where a particular individual may reside, to local hiring practices or employer preferences, or to the state of the local or national economy.4

The medical-vocational rules, set out in a series of “grids,” relate age, education, and past work experience to the claimant's RFC to perform work-related physical activities. Depending on those factors, the grid may direct us to allow or deny a disability claim. For cases that do not fall squarely within a vocational rule, we use the rules as a framework for decision-making. In addition, an adjudicator may rely on a vocational expert to identify other work that a claimant could perform.

How We Determine Disability—The Administrative Process

The Supreme Court has accurately described our administrative process as “unusually protective” of the claimant.5 Indeed, we strive to ensure that we make the correct decision as early in the process as possible, so that a person who truly needs disability benefits receives them in a timely manner. In most cases, we decide claims for benefits using an administrative review process that consists of four levels: (1) initial determination; (2) reconsideration determination; (3) hearing; and (4) appeals.6 At each level, the decision-maker bases his or her decisions on provisions in the Social Security Act (Act) and regulations, as outlined above.

Initial and Reconsideration Determinations

In most States, a team consisting of a State disability examiner and a State agency medical or psychological consultant makes an initial determination at the first level. The Act requires this initial determination.7 A claimant who is dissatisfied with the initial determination may request reconsideration, which is performed by another State agency team. In turn, a claimant who is dissatisfied with the reconsidered determination may request a hearing.8

Hearing Level

We have over 70 years of experience in administering the hearings and appeals process. Since the passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1939, the Act has required us to hold hearings to determine the rights of individuals to old-age and survivors’ insurance benefits.

Over the years, the numbers of ALJs and hearing offices rapidly grew as the Social Security program grew. Recently, we added staff to help us meet growing demand and allow us to focus our resources on those parts of the country with the greatest need for hearings. In addition, we have expanded the use of video hearings, opened five National Hearing Centers to deal only with backlogged cases by video, and realigned the service areas of some of our offices. However, the attributes of the hearings and appeals process have remained essentially the same since 1940. When it established the hearings and appeals process in 1940, the Social Security Board sought to balance the need for accuracy and fairness to the claimant with the need to handle a large volume of claims in an expeditious manner.9 Those twin goals still motivate us. As the Supreme Court has observed, the Social Security hearings system “must be fair—and it must work.”10

When a hearing office receives a request for hearing from a claimant, the case file is prepared by hearing office staff prior to the case being assigned to a judge and scheduled for hearing. The ALJ decides the case de novo, meaning that he or she is not bound by the determinations made at prior levels of the disability process. The ALJ reviews any new medical or other evidence that was not available to prior adjudicators. The ALJ will also consider a claimant's testimony and the testimony of medical and vocational experts called for the hearing. Since the ALJ considers additional evidence and testimony, his or her decision to allow an appeal does not necessarily mean that the earlier decision was incorrect based on the evidence available at the time. If a review of all of the evidence supports a decision fully favorable to the claimant without holding a hearing, the ALJ or attorney adjudicator may issue an on-the-record fully favorable decision.11

In contrast to Federal court proceedings, our ALJ hearings are non-adversarial. Formal rules of evidence do not apply, and the agency is not represented except by the ALJ, who has dual responsibilities.12 At the hearing, the ALJ takes testimony under oath or affirmation. The claimant may elect to appear in-person at the hearing or consent to appear via video. The claimant may appoint a representative (either an attorney or non- attorney) who may submit evidence and arguments on the claimant’s behalf, make statements about facts and law, and call witnesses to testify. The ALJ may call vocational and medical experts to offer opinion evidence, and the claimant or the claimant’s representative may question these witnesses.

If, following the hearing, the ALJ believes that additional evidence is necessary, the ALJ may leave the record open and conduct additional post-hearing development; for example, the ALJ may order a consultative exam. Once the record is complete, the ALJ considers all of the evidence in the record and makes a decision. The ALJ decides the case based on a preponderance of the evidence in the administrative record. A claimant who is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision generally has 60 days after he or she receives the decision to ask the Appeals Council (AC) to review the decision.13

Appeals Council

Upon receiving a request for review, the AC evaluates the ALJ’s decision, all of the evidence of record, including any new and material evidence that relates to the period on or before the date of the ALJ’s decision, and any arguments the claimant or his or her representative submits. The AC may grant review of the ALJ’s decision, or it may deny or dismiss a claimant’s request for review. The AC will grant review in a case if there appears to be an abuse of discretion by the ALJ; there is an error of law; the actions, findings, or conclusions of the ALJ are not supported by substantial evidence; or if there is a broad policy or procedural issue that may affect the general public interest.

If the AC grants a request for review, it may uphold part of the ALJ’s decision, reverse all or part of the ALJ’s decision, issue its own decision, remand the case to an ALJ, or dismiss the original hearing request. When it reviews a case, the AC considers all the evidence in the ALJ hearing record (as well as any new and material evidence), and when it issues its own decision, it bases the decision on a preponderance of the evidence.

If the claimant completes our administrative review process and is dissatisfied with our final decision, he or she may seek review of that final decision by filing a complaint in Federal District Court. However, if the AC dismisses a claimant’s request for review, he or she cannot appeal that dismissal; instead, the ALJ’s decision becomes the final decision.

Federal Level

If the AC makes a decision, it is our final decision. If the AC denies the claimant’s request for review of the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. A claimant who wishes to appeal our final decision has 60 days after receipt of notice of the AC’s action to file a complaint in Federal District Court.

In contrast to the ALJ hearing, Federal courts employ an adversarial process. In District Court, an attorney usually represents the claimant and attorneys from the United States Attorney’s office or our Office of the General Counsel represent the Government. When we file our answer to that complaint, we also file with the court a certified copy of the administrative record developed during our adjudication of the claim for benefits.

The Federal District Court considers two broad inquiries when reviewing one of our decisions: whether we correctly followed the Act and our regulations, and whether our decision is supported by substantial evidence of record. On the first inquiry—whether we have applied the law correctly—the court typically will consider issues such as whether the ALJ correctly evaluated the claimant’s testimony or the treating physician’s opinion, and whether the ALJ followed the correct procedures.

On the second inquiry, the court will consider whether the factual evidence developed during the administrative proceedings supports our decision. The court does not review our findings of fact de novo, but rather, considers whether those findings are supported by substantial evidence. The Act prescribes the “substantial evidence” standard, which provides that, on judicial review of our decisions, our findings “as to any fact, if supported by substantial evidence, shall be conclusive.” The Supreme Court has defined substantial evidence as “such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion.”14 The reviewing court will consider evidence that supports the ALJ’s findings as well as evidence that detracts from the ALJ's decision. However, if the court finds there is conflicting evidence that could allow reasonable minds to differ as to the claimant’s disability, and the ALJ’s findings are reasonable interpretations of the evidence, the court must affirm the ALJ's findings of fact. In practice, courts in many parts of the country do not apply the substantial evidence standard as Congress intended, which results in many inappropriate remands.

If, after reviewing the record as a whole, the court concludes that substantial evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact and the ALJ applied the correct legal standards, the court will affirm our final decision. If the court finds either that we failed to follow the correct legal standards or that our findings of fact are not supported by substantial evidence, the court typically remands the case to us for further administrative proceedings, or in rare instances, reverses our final decision and finds the claimant eligible for benefits.

ALJ Hiring, Management Oversight, and Disciplinary Processes

In order to issue timely, fair, and quality decisions in our hearings and appeals process, we must have the appropriate tools to hire, manage, and discipline our judge corps without infringing on their qualified decisional independence.

Hiring Process

On Commissioner Astrue’s watch, we have raised the standards for ALJ selection, hiring people who we believe will take seriously their responsibility to the American public. We have hired 794 judges since 2007. Insistence on the highest possible standards in judicial conduct is a prudent investment for taxpayers, especially since ALJs may be removed only for good cause established and determined by the Merit Systems Protection Board.

We originally planned to hire 125 ALJs in September of FY 2012; however, we ultimately decided to hire 46 judges who will report on September 23, 2012.

We depend on OPM to provide us with a register of qualified ALJ candidates. During the Azdell litigation, which began in the late 1990s, use of the register was temporarily frozen due to an MSPB decision that was subsequently overturned by the United States Court of Appeals in 2003 (at which time OPM was able to reopen the then-existing register to agency requests for certificates). Since 2003, however, OPM not only re- opened the then-existing register, but also established a new examination, administered it three times, generally, beginning in 2007, and established (and subsequently supplemented) a new register. For our hearing process to operate efficiently, we need ALJs who can treat people with dignity and respect, be proficient at working electronically, handle a high-volume workload without sacrificing quality, and make swift and sound decisions in a non-adversarial adjudication setting.

OPM should continue to engage the agencies who hire ALJs and some authoritative outside groups, such as the Administrative Conference of the United States and the American Bar Association, to incorporate their expertise in the ALJ examination process. I would like to point out that the total number of Federal ALJs is 1,726 as of March 2012, and our corps represents about 86 percent of the Federal ALJ corps—we have the greatest stake in ensuring that the criteria and hiring process meet our needs, but recognize that OPM is required to produce an examination that meets the needs of the Government – and the public it serves – as a whole, pursuant to congressional directives.

Management Oversight and Disciplinary Processes

Under Commissioner Astrue’s leadership, we have not hesitated to hold ALJs accountable where the law permits. Although the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) does not expressly state that ALJs must comply with the statute, regulations, or sub- regulatory policies and interpretations of law and policy articulated by their employing agencies, both the courts15 and the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel16 have opined that ALJs are subject to the agency on matters of law and policy.

One of Congress’ goals in passing the APA was to protect the due process rights of the public by ensuring that impartial adjudicators conduct agency hearings. Employing agencies are limited in their authority over ALJs, and Federal law precludes management from using many of the basic tools applicable to the vast majority of Federal employees. Specifically, OPM sets ALJs’ salaries independent of agency recommendations or ratings. ALJs are exempt from performance appraisals, and they cannot receive monetary awards or periodic step increases based on performance. In addition, our authority to discipline ALJs is restricted by statute. We may take certain measures, such as counseling or issuing a reprimand, to address ALJ underperformance or misconduct. However, we cannot take stronger measures against an ALJ, such as removal or suspension, reduction in grade or pay, or furlough for 30 days or less, unless the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) finds that good cause exists.17

We have taken affirmative steps to address egregiously underperforming ALJs. With the promulgation of our “time and place” regulation, we have eliminated arguable ambiguities regarding our authority to manage scheduling, and we have taken steps to ensure that judges are deciding neither too few nor too many cases. By management instruction, we have limited assignment of new cases to no more than 1,200 cases annually.

Our Hearing Office Chief Administrative Law Judges (HOCALJ) and Hearing Office Directors work together to identify workflow issues. If they identify an issue with respect to an ALJ, the HOCALJ discusses that issue with the judge to determine whether there are any impediments to moving the cases along in a timely fashion and advise the judge of steps needed to address the issue. If necessary, the Regional Chief ALJ and the Office of the Chief ALJ provide support and guidance.18

Generally, this process works. The vast majority of issues are resolved informally by hearing office management. When they are not, management has the authority to order an ALJ to take a certain action or explain his or her actions. ALJs rarely fail to comply with these orders. In those rare cases where the ALJ does not comply, we pursue disciplinary action. Our overarching goal is to provide quality service to those in need and instill that goal in all of our employees, including ALJs.

The current system limits how we address the tiny fraction of ALJs who hear only a handful of cases or engage in misconduct. A few years ago, we had an ALJ in Georgia who failed to inform us, as required, that he was also working full-time for the Department of Defense. Another ALJ was arrested for committing a serious domestic assault. We were able to remove these ALJs, but only after completing the lengthy MSPB disciplinary process that lasts several years and can consume over a million dollars of taxpayer resources.19 In each of these cases, unlike disciplinary action against all other civil servants, the ALJs received their full salary and benefits until the case was finally decided by the full MSPB—even though they were not deciding cases. We are open to exploring options to address these issues, while ensuring the qualified decisional independence of these judges.

Conclusion

Our highly-trained disability adjudicators follow a complex process for determining disability according to the requirements of the law as designed by Congress. I look forward to reviewing the Subcommittee’s report concerning 300 disability cases. Without having seen the report, I will do my best to answer any questions you may have today. Although the report will be severely limited by the statistically non-representative sample of cases that was studied, I am nonetheless hopeful that the report will identify data that merit further research.

________________________________________________________

1 Section 223(d) of the Act defines “disability” as “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months; or in the case of an individual who has attained the age of 55 and is blind (within the meaning of ‘blindness’ as defined in section 216(i)(1)), inability by reason of such blindness to engage in substantial gainful activity requiring skills or abilities comparable to those of any gainful activity in which he has previously engaged with some regularity and over a substantial period of time. An individual shall be determined to be under a disability only if his physical or mental impairment or impairments are of such severity that he is not only unable to do his previous work but cannot, considering his age, education, and work experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work which exists in the national economy, regardless of whether such work exists in the immediate area in which he lives, or whether a specific job vacancy exists for him, or whether he would be hired if he applied for work. For purposes of the preceding sentence (with respect to any individual), ‘work which exists in the national economy’ means work which exists in significant numbers either in the region where such individual lives or in several regions of the country. In determining whether an individual’s physical or mental impairment or impairments are of a sufficient medical severity that such impairment or impairments could be the basis of eligibility under this section, the Commissioner of Social Security shall consider the combined effect of all of the individual’s impairments without regard to whether any such impairment, if considered separately, would be of such severity. If the Commissioner of Social Security does find a medically severe combination of impairments, the combined impact of the impairments shall be considered throughout the disability determination process. An individual shall not be considered to be disabled for purposes of this title if alcoholism or drug addiction would (but for this subparagraph) be a contributing factor material to the Commissioner’s determination that the individual is disabled. For purposes of this subsection, a ‘physical or mental impairment’ is an impairment that results from anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities which are demonstrable by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques.”

2 For blind persons, the SGA earnings limit is currently $1,690 a month. Currently, other disabled persons are engaging in SGA if they earn more than $1,010 a month. Both SGA amounts are indexed annually to average wage growth, using the National Average Wage Index. However, the Act specifies that we cannot necessarily count all the person’s earnings. For example, we deduct impairment-related work expenses when we consider whether a person is engaging in SGA.

3 Under those regulations, we will give controlling weight to a treating physician's opinion if it is well-supported by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and is not inconsistent with the other substantial evidence in the record. In that case, a disability adjudicator must adopt a treating source's medical opinion regardless of any finding he or she would have made in the absence of the medical opinion.

4 43 Fed. Reg. 55349, 55350 (1978) (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 544, 90th Congress, 1st Sess., at 30 (1967)).

5 Heckler v. Day, 467 U.S. 104 (1984).

6 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.900, 416.1400. My testimony focuses on disability determinations, but the review process generally applies to any appealable issue under the Social Security programs.

7 Sections 205(b) and 1631(c)(1)(A) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(b), 1383(c)(1)(A).

8 For disability claims, 10 States participate in a “prototype” test under 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.906, 416.1406. In these States, we eliminated the reconsideration step of the administrative review process. Claimants who are dissatisfied with the initial determinations on their disability cases may request a hearing before an ALJ. The 10 States participating in the prototype test are Alabama, Alaska, California (Los Angeles North and West Branches), Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, and Pennsylvania.

9 Basic Provisions Adopted by the Social Security Board for the Hearing and Review of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Claims, at 4-5 (January 1940).

10 Richardson v. Perales, 402 U.S. 389, 399 (1971).

11 Under the Attorney Adjudicator program, our most experienced attorneys spend a portion of their time making on-the-record, disability decisions in cases where enough evidence exists to issue a fully favorable decision without waiting for a hearing. 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.942, 416.1442.

12 Starting in the 1970s under Commissioner Ross, we tried to pilot an agency representative position at select hearing offices. However, a United States District Court held that the pilot violated the Act, intruded on ALJ independence, was contrary to congressional intent that the process be “fundamentally fair,” and failed the constitutional requirements of due process. Salling v. Bowen, 641 F. Supp. 1046 (W.D. Va. 1986). We subsequently discontinued the pilot due to the testing interruptions caused by the Salling injunction, general fiscal constraints, and intense congressional opposition. Congress originally supported the project; however, we experienced significant congressional opposition once the pilot began. For example, Members of Congress introduced legislation to prohibit the adversarial involvement of any government representative in Social Security hearings, and 12 Members of Congress joined an amicus brief in the Salling case opposing the project.

13 The Appeals Council is headquartered in Falls Church, Virginia. It is our last administrative decisional level. Created on March 1, 1940 as a three-member body, the Appeals Council was established to oversee the hearings and appeals process, promote national consistency in hearing decisions made by referees (now ALJs) and ensure that the Social Security Board's (now the Commissioner's) records were adequate for judicial review. The Appeals Council has grown over time due to the growth in the increasingly complex programs it reviews and the increased number of requests for review that it receives. Currently, the Appeals Council is made up of approximately 75 Administrative Appeals Judges, 56 Appeals Officers, and several hundred support personnel. The Appeals Council is physically located in Falls Church, Virginia with additional offices in Crystal City, Virginia, and in Baltimore, Maryland. Cases originate in hearing offices throughout the country. The Appeals Council looks at each case in which a request for review is filed (over 173,000 in FY 2011). The Appeals Council may grant, deny, or dismiss a request for review. If the Appeals Council grants the request for review, it will either decide the case or return ("remand") it to an ALJ for a new decision. The Council also performs quality review, policy interpretations, and court-related functions. The Appeals Council is the core component of the Office of Appellate Operations, one of the parts of our Office of Disability Adjudication and Review. The Office of Appellate Operations provides professional and clerical support for the Appeals Council, and also maintains and controls files in cases decided adversely to claimants by ALJs and the Appeals Council, in case a further administrative or court appeal is filed. When a claimant brings a civil action against the Commissioner seeking judicial review of the agency’s final decision, staff in the Office of Appellate Operations prepare the record of the claim for filing with the Court. This includes all the documents and evidence the agency relied upon in making the decision or determination.

14 Consolidated Edison Co. of New York v. N.L.R.B., 305 U.S. 197 (1938).

15 “An ALJ is a creature of statute and, as such, is subordinate to the Secretary in matters of policy and interpretation of law.” Nash v. Bowen, 869 F.2d 675, 680 (2d Cir.) (citing Mullen, 800 F.2d at 540-41 n. 5 and Association of Administrative Law Judges v. Heckler, 594 F. Supp. 1132, 1141 (D.D.C. 1984)), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 812 (1989).

16 “Administrative law judges have no constitutionally based judicial power. . . . As such, ALJs are bound by all policy directives and rules promulgated by their agency, including the agency's interpretations of those policies and rules. . . . ALJs thus do not exercise the broadly independent authority of an Article III judge, but rather operate as subordinate executive branch officials who perform quasi-judicial functions within their agencies. In that capacity, they owe the same allegiance to the Secretary's policies and regulations as any other Department employee.” Authority of Education Department Administrative Law Judges in Conducting Hearings, 14 Op. Off. Legal Counsel 1, 2 (1990).

17 The MSPB makes this finding based on a record established after the ALJ has an opportunity for a hearing.

18 Our managerial ALJs play a key role in ALJ performance. They provide guidance, counseling, and encouragement to our line ALJs. However, the current pay structure does not properly compensate them. For example, due to pay compression, a line ALJ in a Pennsylvania hearing office can earn as much as our Chief Administrative Law Judge. Furthermore, our leave rules limit the amount of annual leave an ALJ can carry over from one year to the next. These compensation rules discourage otherwise qualified ALJs from pursuing management positions, and the APA prevents us from changing those rules.

19 Since 2007, we have filed removal charges with the MSPB against nine ALJs. The MSPB upheld our removal charges against five ALJs; three ALJs left the agency or retired in lieu of removal. One removal action is currently awaiting a decision from the MSPB. Additionally, from 2007 to present, we either sought to file or filed charges seeking suspension against 29 ALJs. Of these ALJs, 22 were suspended, six either retired or separated from the agency; and one case is currently before the MSPB.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hearing Office Chief Administrative Law Judge

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Hearing Office

Office of Disability Adjudication and Review

before the Senate Committee on

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

September 13, 2012

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Coburn, Members of the Subcommittee:

My name is Douglas Stults, and I serve as the Hearing Office Chief Administrative Law Judge (HOCALJ) for the ODAR Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Hearing Office (HO). I have four years and five months of experience as an ALJ and three years and nine months experience as a HOCALJ. Prior to becoming an administrative law judge (ALJ), I worked for ODAR in the Oklahoma City HO for 12 years, 3 years as the Hearing Office Director (HOD), 5 years as a Group Supervisor, and 4 years as an Attorney-Advisor. Prior to working for ODAR, I was a staff attorney for the UAW Legal Services Plan in Oklahoma City for 7½ years and had practiced law in central Oklahoma for 8½ years before that.

The Oklahoma City HO primarily serves central and western Oklahoma, specifically Oklahoma City, Lawton, Ardmore, and Clinton, Oklahoma, as well as Wichita Falls, Texas and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Thus, the claimants served by the Oklahoma City HO live in urban, suburban, and rural areas and are of diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

The Oklahoma City HO is presently staffed with 13 ALJs, supported by 59 staff, specifically: 1 Hearing Office Director; 4 Group Supervisors; 1 Administrative Assistant; 2 Hearing Office Systems Administrators; 12 Senior Attorneys; 3 Attorney-Advisors; 6 Paralegal-Analysts; 3 Lead Case Technicians; 13 Senior Case Technicians; 6 Case Technicians; 4 Case Intake Assistants; and 2 Contact Representatives. Fifty-seven percent of our employees (41 of 72) have 6 or more years of ODAR experience and 39% (28 of 72) have 16 or more years, myself included.

In fiscal year (FY) 2011, the Oklahoma City HO attained our regionally-set dispositional goal, with 7,216 claimants served. We also completed all of our aged cases (750 days old). Thus far in FY 2012, we have served 6,317 claimants. Through the end of July 2012, Oklahoma City ALJs’ dispositions have averaged: 37.8 percent fully favorable; 3.2 percent partially favorable; 41.7 percent unfavorable; and 17.2 percent dismissals. Further, through the end of August 2012, the Oklahoma City HO has:

Average Processing Time of 381 days;

Average Cases Pending per ALJ of 591;

Average Age of Pending Cases of 258 days;

Cases under 365 days old of 76%;

Receipts per day per ALJ of 2.31;

Hearing Scheduled per day per ALJ of 2.39;

Hearings Held per ALJ per day of 1.79;

Held to Scheduled Ratio of 75%;

2 Dispositions per day per ALJ of 2.15; and

Dispositions to Receipt Ratio of 103%.

As the HOCALJ, I strive to ensure that my hearing office handles hearing requests in an orderly manner. I discuss ALJ workload and case assignment regularly with our HOD, who oversees the direction of our staff involved in preparing cases for hearing. Generally, cases are “worked-up” for hearing in hearing request date order, with the oldest cases prepared first. Our HOD randomly assigns a minimum number of cases to each Oklahoma City ALJ; 40 cases per month so far in FY 2012.

I use our agency’s technology to manage performance, quality, and productivity, mainly with the help of the Case Processing Management System (CPMS) and Disability Adjudication Reporting Tools (DART), including the “How MI Doing” and ODAR Management Information Dashboard (ODAR MIND). Top priorities include the handling of our oldest cases, the number of hearings scheduled and held per ALJ, the pending per ALJ, and the monthly dispositional totals. I pass general information concerning these categories onto all ALJs, and pass specific information on to individual ALJs as necessary.

I endeavor to work closely with our Oklahoma City ALJs. I have an unconditional “open door” policy. I speak with all of our ALJs, both formally and informally, concerning questions, problems, or suggestions that they might have, regarding individual cases as well as office policies and procedures. I regularly send e-mails to clarify issues and procedures for our ALJs and share general information.

Let me emphasize that while I can take actions to ensure that ALJs move their caseloads and apply the law and our policies correctly, the Administrative Procedure Act grants all ALJs “qualified decisional independence.” “Qualified decisional independence” means that ALJs must be impartial in conducting hearings. They must decide cases based on the facts in each case and in accordance with the agency’s policy, as set out in the regulations, rulings, and other policy statements. It also means, however, that ALJs make their decisions free from agency pressure or pressure by a party to decide a particular case, or a particular percentage of cases, in a particular way. If I see a performance or quality issue with an ALJ that I need to address, I will discuss the issue with the judge as soon as possible to ensure that the ALJ’s actions are consistent with the agency’s policy, and that the ALJ is performing at an acceptable level of productivity. While I exercise appropriate management oversight over the ALJs in my office and can take a number of actions to help ALJs improve their performance, I cannot and do not interfere with or influence the ultimate decision in any case.

In addition to my managerial duties, I hold hearings for disability cases.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I would be happy to answer any questions that you may have.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hearing Office Chief Administrative Law Judge

Roanoke, Virginia Hearing Office

Office of Disability Adjudication and Review

before the Senate Committee on

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

September 13, 2012

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Coburn, Members of the Subcommittee:

My name is Thomas Erwin, and I serve as the Chief Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) for the Roanoke, Virginia hearing office (HO). I have a little more than 3 years of experience as an ALJ and 1 ½ years as a hearing office chief ALJ (HOCALJ). Prior to becoming an ALJ, I was an attorney advisor in the Roanoke, Virginia Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR) office for three years. Before joining the Social Security Administration, I served as a U. S. Navy JAG attorney on active duty for five years in San Diego and Port Hueneme, California, and was appointed as the Officer in Charge of the Naval Legal Service Office Branch Office in Port Hueneme. One of my duties in the Navy was to serve as criminal defense counsel in courts- martial cases; so yes, Tom Cruise did play me in the movie A Few Good Men. I then worked in private practice in Southern California as a certified specialist in family law prior to joining the Social Security Administration in 2006.

The Roanoke, Virginia HO serves a broad area of Southwest Virginia and Southeast West Virginia. This service area is a part of a cultural region commonly known as Appalachia. The region's economy, once highly dependent on mining, forestry, agriculture, chemical industries, and heavy industry, has become more diversified in recent times.

The Roanoke Hearing Office has eight ALJs, three of whom have fewer than two years of experience on the job. The newest judge has been with the office only since June of this year. The office has had significant ALJ turnover over the past several years, and has lost eight judges to retirement or transfer. SSA has assigned eight new judges in the same period; seven of these judges were new to the position or had less than one year of experience as an ALJ when they reported. The office has 48 employees.

For fiscal year 2012, through August, the Roanoke hearing office has received 3,690 hearing requests, an average of 335 cases per month. We have issued 3,643 decisions, so we have processed close to 99% of total receipts. We have just under 4,700 cases pending in our office, an average of over 580 cases pending per judge. Our average processing time is 432 days from the request for hearing to decision.

The Roanoke hearing office has an allowance rate of 57% for fiscal year 2012. The judges have an allowance rate of 55%, with most judges having an allowance rate between 45 and 57%. The difference in allowance percentage between the overall office rate and the judges represents favorable decisions processed by our senior attorneys.

As a HOCALJ, it is my job to make sure that the office functions smoothly, and that we process cases fairly and efficiently. I strive to ensure that my hearing office handles hearing requests in an orderly manner. I work with three other office managers to make sure cases are worked up and ready for a hearing, that they are assigned to judges to allow them to hold hearings, and that writers draft legally sufficient decisions. I monitor the workloads of the judges to make sure they have sufficient cases at various stages of the process to allow them to review cases before scheduling, hold hearings, and issue decisions. A hearing office has many working parts, all of which need to operate smoothly to maintain both quality and productivity. The senior case technicians prepare the files and get them ready for hearing; the judges hold the hearings; and then the writers must draft, based on directions they receive from the judges, legally sufficient and defensible decisions. As HOCALJ, I work with my fellow supervisors to manage performance, quality, and productivity at each phase of a case’s development and resolution.

I work with the ALJs in the office to make sure they are aware of monthly and yearly goals, that they move cases through each stage of the process in a timely manner, and that they issue quality decisions as quickly as possible. If the judges are having a problem, I help them resolve the issue so that they can continue doing their job. I try to lead by example.

Let me emphasize that while I can take actions to ensure that ALJs move their caseloads and apply the law and our policies correctly, the Administrative Procedure Act grants all ALJs “qualified decisional independence.” “Qualified decisional independence” means that ALJs must be impartial in conducting hearings. They must decide cases based on the facts in each case and in accordance with the agency’s policy, as set out in the regulations, rulings, and other policy statements. It also means, however, that ALJs make their decisions free from agency pressure or pressure by a party to decide a particular case, or a particular percentage of cases, in a particular way. If I see a performance or quality issue with an ALJ that I need to address, I will discuss the issue with the judge as soon as possible to ensure that the ALJ’s actions are consistent with the agency’s policy, and that the ALJ is performing at an acceptable level of productivity. While I exercise appropriate management oversight over the ALJs in my office and can take a number of actions to help ALJs improve their performance, I cannot and do not interfere with or influence the ultimate decision in any case.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I would be happy to answer any questions that you may have.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Regional Chief Administrative Law Judge

Atlanta Region

Office of Disability Adjudication and Review

before the Senate Committee on

Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

September 13, 2012

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Coburn, Members of the Subcommittee:

My name is Ollie L. Garmon, III, and I serve as the Regional Chief Administrative Law Judge (RCALJ) for Region IV (Atlanta). The Montgomery, Alabama hearing office (HO) is one of the offices in the Atlanta region. I have 21 years’ experience as an ALJ, 3 years as a Hearing Office Chief ALJ (HOCALJ), 4 years as the Assistant to the RCALJ, and 9 years as the RCALJ.

As an RCALJ, I provide general oversight for all program and administrative matters concerning our hearings process in the Atlanta region. The Atlanta region is composed of 37 hearing offices, nearly 400 administrative law judges, and a total staff of nearly 2,300 people in following eight states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. This region serves a population of about 60 million citizens. We have approximately 25 percent of the agency’s hearings caseload, which results in more than 200,000 decisions per year.

I began my legal career in the private sector as an associate for a law firm; I then became a sole practitioner, after which I organized and was a partner in a law firm. During this same time, I served in the public sector as a city attorney and was elected county prosecuting attorney for a 4- year term. In 1979, I was elected for a 4-year term to a full time judicial position of county court judge where I also served as a juvenile court judge. Afterwards, I was appointed by the Governor of the State of Mississippi to the position of Commissioner of the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Commission for a 6-year term.

One of the Hearing Offices in Region IV is located in Montgomery, Alabama. The Montgomery Office’s service area includes Alexander City, Anniston, Auburn, Demopolis, Montgomery, Opelika, Selma, and Tuskegee.

The Montgomery Office currently has 10 judges. We expect two new judges to report for duty on September 24, 2012. The support staff for the ALJs includes a mix of attorney advisors, paralegal specialists, and legal assistants. The office has a high transfer rate for ALJs, who frequently request reassignment to other offices.

In fiscal year (FY) 2011, the Montgomery Office received 8,357 cases for adjudication and issued 7,252 dispositions. In FY 2012 to date, the office has received 6,540 cases for adjudication and issued 6,246 decisions. The Montgomery Office currently has 8,323 cases pending and the current average processing time is 430 days. The rate of average dispositions per ALJ per day is 2.37. .

Let me emphasize that while I can take actions to ensure that ALJs move their caseloads and apply the law and our policies correctly, the Administrative Procedure Act grants all ALJs “qualified decisional independence.” “Qualified decisional independence” means that ALJs must be impartial in conducting hearings. They must decide cases based on the facts in each case and in accordance with the agency’s policy, as set out in the regulations, rulings, and other policy statements. It also means, however, that ALJs make their decisions free from agency pressure or pressure by a party to decide a particular case, or a particular percentage of cases, in a particular way. If I see a performance or quality issue with an ALJ that I need to address, I will 2 discuss the issue with the judge as soon as possible to ensure that the ALJ’s actions are consistent with the agency’s policy, and that the ALJ is performing at an acceptable level of productivity. While I exercise appropriate management oversight over the ALJs in my offices and can take a number of actions to help ALJs improve their performance, I cannot and do not interfere with or influence the ultimate decision in any case.

Thank you for the opportunity to be here today. I would be happy to answer any questions that you may have.